The dance of mythos and logos

Or, what happens when rationality is elevated to cult status over imagination

“Vision without action is a dream; action without vision is a nightmare.”

The British storyteller Martin Shaw says the stories we most need now arrived right on schedule, three thousand years ago. Mythic stories remind us of our reciprocity with the whole of life and help us to imagine our true purpose. Stories of human frailty and creativity, of our humility and daring, wickedness and perseverance show us in robust, messy context. For nearly all of human existence we’ve understood ourselves as but one of many characters in the tale. And yet our current cultural story casts us as the exceptional species in charge of, and entitled to, everything.

Early on, the Greeks embraced two fundamentally different and necessary ways of being in the world: logos and mythos. Logos is factual, practical, the mode of thought we use to get something done and achieve greater control over our environment. In the Enlightenment, intellectuals and scientists denigrated myth in favor of pragmatics, efficiency and rational proof. This has proven to be a mistake.

Mythos is not an inferior mode of thought, nor an early, misguided attempt at history. Mythic tales never claim to be objective fact. A myth is true because it is effective, not because it gives us factual information, but because it’s a guide, inviting us to change our minds and hearts.

Shaw says, “Myth is the power of a place, speaking.” We belong to places, not the other way around.

I love cities. I’ve lived in and visited some great ones. I abhor and shun ugly, paved suburban environments. Sadly, my commute to the university campus where I teach takes me down an ugly 4-lane feeder road past ugly shopping centers and bleak townhouses to an ugly 6-lane highway, eventually to a trying-not-to-be-ugly 5-story parking garage.1 There’s no train or bus, so I drive.

Environments like this exist because for the past three or four hundred years, logos has bulldozed mythos into a wetland and paved it over. It’s well past time to demolish the asphalt, return it to the pit of hell from whence it came, and lovingly restore the delicate, dynamic balance of logos and mythos that until recently guided the human experience.

In her wonderful book, A Short History of Myth, Karen Armstrong observes that humans fall easily into despair. From the very beginning, we invented stories that placed our lives in a larger setting, one that revealed underlying patterns and gave us a sense that against all the depressing and chaotic evidence to the contrary, life had meaning and value. Myth is not a story told for its own sake. It shows us how we should behave by putting us in the correct spiritual or psychological posture for right action in this world or the next.

“[Myth is] a game that transfigures our fragmented, tragic world and helps us to gauge new possibilities by asking ‘what if?’ a question which has also provoked some of our most important discoveries in philosophy, science and technology.”

The impoverishment of our built environment stems from this elevation of logos over its partner mythos. Reason and facts are prized over meaning and context. Logos sends us looking for capital T Truth in news items instead of mythic tales. The very crisis of the fact-free world of lies and gaslighting we now inhabit points to the inadequacy of logos alone to make sense of the world. Sadly, mythos has been buried for so long, we can’t even visualize its relevance.

As for the importance of mythos in the physical world, I’ve written elsewhere that architecture must mean something beyond serving basic functions like shelter and commerce. As with any work of art or literature, there’s a theme within the piece, a purpose for telling the tale, an alignment with mythos.

In the first century BCE, back when mythos and logos still enjoyed equal billing, a Roman architect and engineer called Vitruvius wrote an architectural treatise called The Ten Books on Architecture.2 It’s an interesting read. The most quoted principles are the triumvirate: firmitas, utilitas, and venustas, or “firmness, commodity, and delight.” Vitruvius argued that architecture must be structurally sound, functional, and beautiful—all three. It must serve a purpose both practical and spiritual. Though human cultures and their architectural styles have taken many different forms over the centuries, these underlying principles have generally held.

Until recently, when logos vanquished mythos. Then the unraveling began.

“The intuitive mind is a sacred gift and the rational mind is a faithful servant. We have created a society that honors the servant and has forgotten the gift.” ~ Einstein

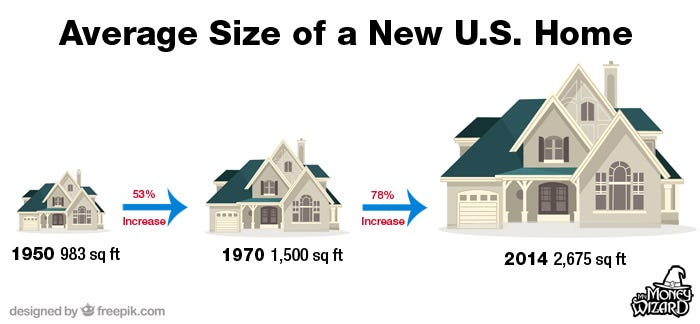

Rationality was elevated to cult status over imagination, which is why we’re surrounded by more quantity than quality. Just look at most “real estate development” in the U.S. since the 1950s. A simple chart of house sizes since Levittown proves the point.3

American real estate favors size and cheap construction over any of Vitruvius’ imperatives. Buildings and land itself are commodities. Junk thrown up with no regard for the human spirit. Your Targets, your Walmarts, your suburban townhouses shoehorned into the last forested strip of land between Target and Walmart. Mass-built single-family housing is rarely designed by architects. In less than one hundred years, architects have slipped from being indispensable to the built environment to mostly catering to the 1%.4

As an architecture teacher, I will always keep the eternal flame of mythos lit. To experience a well-designed place is to feel the shimmering presence of timeless principles. I don’t need to have studied the phenomenology of Bachelard and Heidegger to notice and appreciate the unconscious psychological effects of a place on my body and spirit. Principles of refuge and prospect, enclosure and expansion echo the caves and trees in which humans evolved, the mythic connections to our origins in the natural world.

Good architects care deeply about the expression of center, edge, verticality, and horizontality, defined boundaries and connection to spaces beyond. We tap into ancient narratives of shelter, light and shadow, orientation to the sun and views, connection between inside and outside, the power of thresholds. We create a hierarchy of spaces for gathering and for privacy, to hold community and protect individuals. Action and contemplation. Procession, ascent and descent mirror movements across millennia.

Proportion guides all the arts, including music and dance and architecture. Proportion describes relationships between and among elements, derived not only from the human body, but from all of nature. The nautilus shell, the curve of a bird’s wing, the repetition and structure of leaves, the inside of an orange, the rhythm of a heartbeat, the branching of tree limbs and lung bronchiole—these all stem from the wondrous seeds of universal mathematical proportions.

“Music is liquid architecture. Architecture is frozen music.” ~ Goethe

In modern Rome stands the Pantheon, a marvel built in the heart of the city in the 2nd century. The coffered dome is concrete. Stones used in the concrete mix vary from travertine and old terracotta tiles to lighter tufa and pumice near the top (clever Romans). The dome is twenty-one feet thick at its base atop the round wall, four feet thick around the open oculus. It weighs 4,500 metric tons. In architecture school, we learned that the Pantheon marked the city as the center of the universe. The open oculus connects heaven and earth.

When I leave the dusty, hot, noisy city and enter the hushed cool, I’m awestruck. The place hums with a vibration that seems to be everywhere and nowhere. Modern voices echo as whispers from the past. The blue Roman sky penetrates the great oculus at the top. A solid shaft of sunlight ignites a circle on the floor that waters my eyes. Marble blocks in white, ochre, slate and sienna form a pattern of squares and circles. Surely, the sun would burn a hole through any other material.

I stand at the circle’s bright edge, about to dive in and surrender to the light. And then—can it be?—the circle crawls across one color of marble into another. The sense of this movement dizzies me. I am seized for the first time in my life with the bodily certainty that I stand on a planet, hurtling at inconceivable speed through space around a giant star.

I lose myself watching the spot creep its slow journey across the floor. I tell people—a mother with a young son, a group of four twenty-somethings reading to each other in English from a guidebook. I want them to be as awestruck as I am. They seem to appreciate being in on the secret. Their wonder lights me up.

Before the Pantheon was built, the sun shone everywhere without discrimination. The Romans hoisted all that concrete up into their blue sky to honor the sacred forever.

“The sun does not realize how wonderful it is until after a room is made.”

~ Louis I. Khan, American architect, 1901 - 1974

This revelation of the hidden seems like a miracle, and it is. It’s also in our nature to create such places—places that stir the soul and awaken our sense of belonging. We have the capacity to call down the sacred into our midst, to honor the mystery that enfolds us. Without such places, we are unconscious and homeless.

The mythic stories are still here, all around us and within us, hidden beneath everything we do. Like the moving spot of sunlight in the Pantheon, I know there is more happening around me than I usually notice. It feels like pure grace when I do, though, a moment worthy of celebration. A moment I want to share, as I’m sharing with you, dear reader.

I imagine myself moving through time and space in a thin zone between the known and the numinous. This is the dance of mythos and logos. It’s a dance I need, a dance I long for, whether I’m aware of it or not. When I embrace it, it saves me.

Julie Gabrielli writes Homecoming, a place to step out of the center, explore the edges, and share our profound gratitude, awe, and wonder at being alive on this amazing planet.

The solar panels on the roof are a nice touch, but they’re lipstick on a pig.

De Architectura is described here.

I exaggerate, but look at any recent American houses on ArchDaily and you get the idea.