Welcome to Talking Back to Walden. This is where we consider only the best passages of Thoreau’s 1854 classic, for what they might tell us about our present-day environmental woes and hopes. This month, as the weather grows colder here in North America, we explore our animal affinity with the places we call home.

Thanks to

for your wise counsel and encouragement on this “Talking Back” essay. And I’m always inspired by ’s beautiful, openhearted meditations on home.From chapter 1, Economy

In this chapter, Thoreau has much to say about the origins of human shelter. His takes resemble some of the 18th and 19th century architectural theorists I’ve written about. Though he’s less concerned with demonstrating material origins of architectural form than with comparing what he calls the “primitive” dwellings of “savages” with those of so-called civilization. By the measures of cost, self-sufficiency and freedom, he finds the modern approach wanting.

We know Thoreau as a ground-breaking environmental writer. Who knew he was also an early advocate for affordable housing?

The transcript is at the end, if you prefer to read it.

Talking Back

I’m cheating on an eighteen-year relationship that has seen me through a good chunk of my adult life—through terrifying mental illness, two dog deaths, a pandemic and an earthquake. Losing my father, my mother eight months later, marital estrangement and Lego world-building. Shelter, Thoreau calls it. A house, architects call it. Home, says everyone else.

Designing a house is magical. The early concept sketches are visual stories. How the house nestles into the hilltop. The conversation of porch columns and trees. Relationships between rooms and people and times of day and year. Light. Air movement. Views. Wood, stone, glass. A family’s daily patterns trace from place to place, surprise discoveries breathe life into rooms.

The sun raking across a table, a floor. You start with words, ideas, needs, wants. Trace lines on paper, telling stories to yourself. The lines raise questions: what if we try it this way? Or this way? What’s it about, really? Can I ever get it right? How can necessity become art? Will I remember that mistakes are treasures?

“The architect’s two most important tools are: the eraser in the drafting room and the wrecking bar on the site.” ~ Frank Lloyd Wright

Last summer, we rented a little split-level in a city 45 miles away to see if we like it enough to leave the city where we’ve lived for over thirty years. It sounds practical on paper. Move some furniture, kitchenware, clothing and artwork on a holiday weekend. Set up shop, see how it feels. Like an AirBnb, but with our stuff.

When I return to our old house to retrieve something else we forgot, I’m uneasy. I feel empty loneliness. The bare walls and echoing rooms whisper their resigned accusations. Is this just a fling? Or is it more serious? When are you coming back? What’s wrong with me? I feel guilty. And sad. I have no answers.

I pause on the street, remembering that time when all the neighbors, adults and kids, dug out after two three-foot snowfalls left us stranded.

I stand on the living room rug remembering the weight of our first dog in my lap as the vet injected her, and the cry that erupted from me when she died.

This is the piano in the living room where I learned Ben Folds’ song, “The Luckiest,” to play for my husband on his birthday after too many turbulent years. And the bench where our 10-year-old son sat to sing harmony. And the baffled-embarrassed-squirmy-unreadable expression on my husband’s face as he listened.

This is the smell of wood burning in the living room—with friends on New Year’s Eve, with family on Christmas morning, quiet evenings reading—and downstairs for football and movie night.

These are the smells from the kitchen that’s finally big enough for both of us: chicken roasting, sourdough bread baking, Friday night pizza, Grandma Edie’s spaghetti sauce, stir-fry, short ribs, Mom’s brisket, salmon, Grandma Virgie’s red cabbage, garlic sizzling in hot olive oil, caramelizing onions, apple crisp with heirlooms from the farmer’s market.

This is the counter, site of holiday cooking baking, where kids flung colored sugar and raisins, and sisters reminisced with our mother while the guys watched football.

This is the playroom off the kitchen where our son sang to himself and told stories to his Playmobil guys and Brio trains while I cooked.

This is his bedroom where he and I assembled his big-boy bed from IKEA when his dad was out of town.

And the bed where, every night, we read and sang together.

And the nightstand where he found treasures from the Tooth Fairy—a feather, a shell, a coin.

These are the marks on the door jamb of his closet to record his growth.

This is the windowsill and radiator where he lined up his creations molded from blue beeswax into jet planes and ninja swords.

This is the dark upstairs hall where I sat against the wall in the small hours to grieve my failed business and faltering marriage as more unraveling loomed.

This is the desk where I first understood that I want to be taken care of. And the shame I felt.

This is the window over the desk where I looked out to see a fox trotting east on the sidewalk past Joanne’s house with a squirrel in his mouth.

This is the lavender oil in the bathtub where I spent the summer after Mom died, binge-watching “Lost” and missing the irony completely.

This is the treehouse dining room where we fired up the smoky woodstove and watched the snow fall among the massive old poplar and oaks and beeches, the delicate dogwoods.

This is the back fence I designed after screens of old Kyoto houses, built by the shirtless carpenter who paused his work to dig our first dog’s grave.

This is the precious summer-only sunrise raking across furniture and floor in the north-facing dining room.

This is the library where my husband learned the guitar and our third dog surprised us all by singing along—first to the high-E string, then graduating to a nuanced preference for the blues

.I’m here in the little rented house: same desk, different room, different view, thinking of the house back home. I moved plenty as a kid and young adult, always wrenching and exciting, a new chapter, bring it. This grief is burdened with guilt. How can I bring myself to say to my house, It’s not you, it’s me.

I’m resisting this change, any change, the necessary, inevitable change of our neighbors downsizing and moving on. Our son graduating college and moving out. Dear people who’ve shared the ups and downs of those eighteen years with us. I’ve forgotten that the house is no stranger to goodbyes; we are the second owners. The couple who built it lived there forty-five years. The family that comes after us will breathe new life into its rooms. Maybe they’ll love the trees more than we did. Or successfully cultivate oyster mushrooms, where we managed only shitake.

My nostalgia is self-inflicted, I can’t help it. I miss my poplar tree friend, the two beeches. I miss my view. I miss the street where, one time, beginning a run, I was startled by the close breeze and thwykk of wings—a red-tailed hawk passed over my right shoulder not six feet up and banked left between the trees in search of lunch, her tail a fan of gleaming gold ribbons.

Immersion

Both David Abram and Robin Wall Kimmerer write eloquently about the grounded animacy of ordinary objects. How a pencil, a notebook, even a plastic bottle was once alive. Consider this. Contemplate something close at hand, guided by these words from Abram’s book, Becoming Animal.

Wisdom

“Sitting in a Circle” is one of my favorite chapters in Braiding Sweetgrass. Every time I read it, I want to live in the wilderness and wade in the marsh with Robin Wall Kimmerer. My students love it, too, for its story of undergrads on an immersive study trip building a dome shelter of saplings and cross-braces tied with spruce root and covered with cattail-fiber mats—all gathered, dug and woven by them. Sitting inside the cozy space, they’re like apples in a basket.

“When the last pair of saplings is tied, quiet falls as they see what they have made. It looks like an upside-down bird’s next, a basket of thick saplings domed like a turtle’s back. You want to be inside.”1

David Abram expresses the organic animacy of an ordinary house, something I’ve felt but had no words for. As he relates in Becoming Animal, when his daughter Hannah was born, the house they were renting “was transformed by her arrival in its midst, and by the steady curiosity that she lavished upon even its plainest facets—a single brick in the floor, a patch of painted wall.”2

One day, he arrived home after dropping Hannah and her mother at the airport for a ten-day trip, but something felt strange. “The walls, the ceiling, the low tables, and even the windows were all glaring at me. . . The whole interior felt heavy, oppressive—accusation had turned to dejection.” He spontaneously assured “no one in particular” that the baby Hannah would be home soon, which immediately lightened the mood. The few friends he told the story to assumed he was projecting his own inner mood, but this didn’t sit right with him.

“The notion of ‘projection’ fails to account for what it is about certain objects that calls forth our imagination. It implies that the objects we perceive are purely passive phenomena, utterly neutral and inert, and so enables us to overlook the way in which such objects actively affect the space around them—the manner in which material things are also bodies, influencing the other bodies within their ambit, and being influenced in turn.”3

When it came time to leave that house, Abram grew increasingly anxious. During a moonlit wander through the house, he finally understood.

“It was as though we’d been living for a year and a half in a dense grove of old trees, a cluster of firs, each with its own rhythm and character, from whom our bodies had drawn not just shelter but perhaps even a kind of guidance as we grew into a family. My animal senses had grown accustomed to these beams—to these rectilinear lives whose subtly different dispositions had lent a communal warmth to this structure, instilling the uncanny kinship I’d been feeling with this place.”4

He bid farewell to each wood element by leaning on it, tracing its grain with fingertips and knocking on it with his knuckles—“a clumsy gesture, sure, but an instinctive enough way to make grateful contact with the interior of a piece of wood.”5

Measure

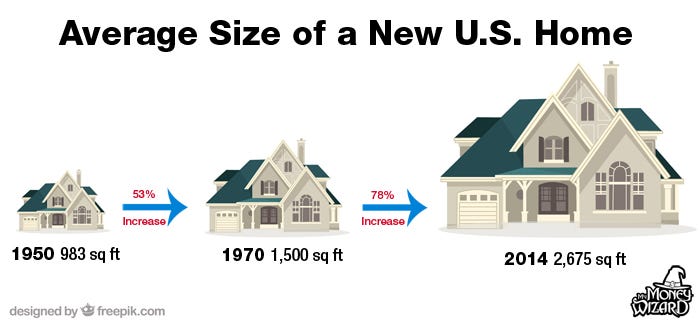

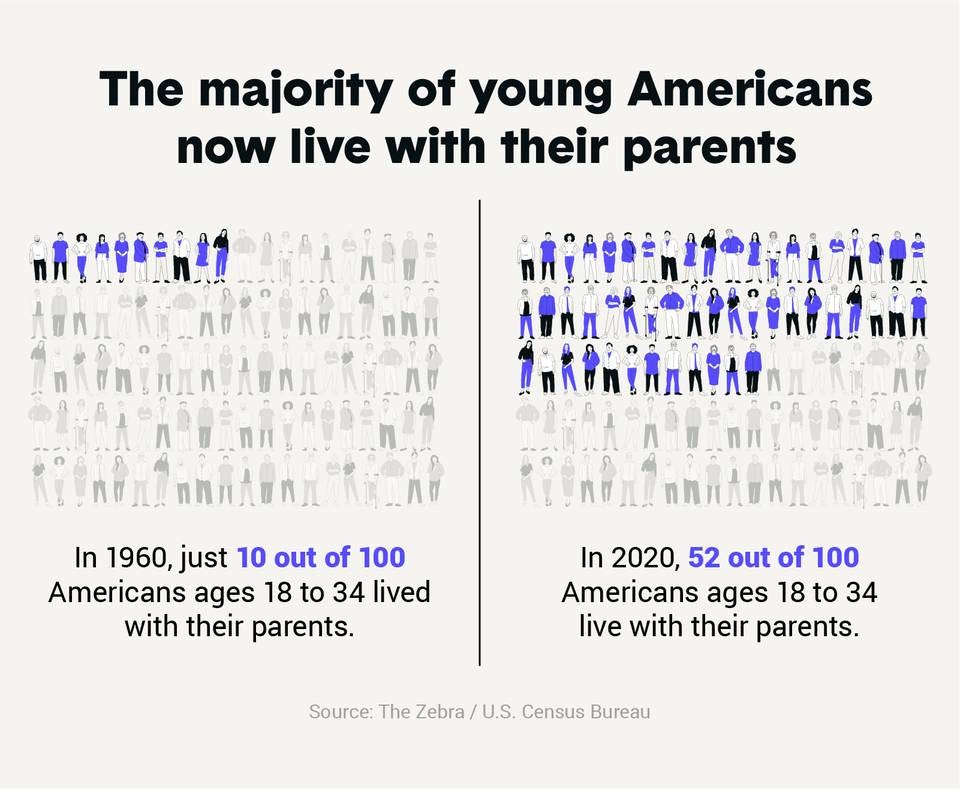

I was planning to write here about the “tiny house” movement, but there’s enough material for an entire post on its own. For now, I’ll share a few statistics about house size and affordability in the U.S.

Talking back to Walden together

Last month in the chat, we collected photos of what autumn looks like where you live. This month, let’s share our encounters with ordinary objects, rooms or even houses, using our animal senses to engage our imaginations. What sort of kinship do you notice? Subscribers can join the fun in this chat.

Transcript of excerpt from Chapter 1, Economy

We may imagine a time when, in the infancy of the human race, some enterprising mortal crept into a hollow in a rock for shelter. Every child begins the world again, to some extent, and loves to stay outdoors, even in wet and cold. It plays house, . . . having an instinct for it. Who does not remember the interest with which, when young, he looked at shelving rocks, or any approach to a cave? It was the natural yearning of that portion, any portion of our most primitive ancestor which still survived in us. From the cave we have advanced to roofs of palm leaves, of bark and boughs, of linen woven and stretched, of grass and straw, of boards and shingles, of stones and tiles. At last, we know not what it is to live in the open air, and our lives are domestic in more senses than we think. From the hearth the field is a great distance. It would be well, perhaps, if we were to spend more of our days and nights without any obstruction between us and the celestial bodies, if the poet did not speak so much from under a roof, or the saint dwell there so long. Birds do not sing in caves, nor do doves cherish their innocence in dovecots.

. . . . I have seen Penobscot Indians, in this town, living in tents of thin cotton cloth, while the snow was nearly a foot deep around them, and I thought that they would be glad to have it deeper to keep out the wind. . . . A comfortable house for a rude and hardy race, that lived mostly out of doors, was once made here almost entirely of such materials as Nature furnished ready to their hands. Gookin, who was superintendent of the Indians subject to the Massachusetts Colony, writing in 1674, says, “The best of their houses are covered very neatly, tight and warm, with barks of trees, slipped from their bodies at those seasons when the sap is up, and made into great flakes, with pressure of weighty timber, when they are green....The meaner sort are covered with mats which they make of a kind of bulrush, and are also indifferently tight and warm, but not so good as the former.... Some I have seen, sixty or a hundred feet long and thirty feet broad.... I have often lodged in their wigwams, and found them as warm as the best English houses.” . . . In the savage state every family owns a shelter as good as the best, and sufficient for its coarser and simpler wants; but I think that I speak within bounds when I say that, though the birds of the air have their nests, and the foxes their holes, and the savages their wigwams, in modern civilized society not more than one half the families own a shelter. In the large towns and cities, where civilization especially prevails, the number of those who own a shelter is a very small fraction of the whole. The rest pay an annual tax for this outside garment of all, become indispensable summer and winter, which would buy a village of Indian wigwams, but now helps to keep them poor as long as they live. . . An average house in this neighborhood costs perhaps eight hundred dollars, and to lay up this sum will take from ten to fifteen years of the laborer’s life, even if he is not encumbered with a family. . . so that he must have spent more than half his life commonly before his wigwam will be earned. If we suppose him to pay a rent instead, this is but a doubtful choice of evils. Would the savage have been wise to exchange his wigwam for a palace on these terms?

Thanks for reading. Read previous months here: September, October.

Talking Back to Walden is a labor of love. If you enjoyed it, please share. For more like this and for my regular posts, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass, p.225.

David Abram, Becoming Animal, p.30.

Abram, p.32

Abram, p.35

Abram, p.35.

I would be the same if I had to say good-bye to my house. Even if I was yearning to live somewhere different a piece of my heart would be here wanting to stay. The energy that seeps into the walls along with the memories. Thank you for sharing the images and thoughts of your beautiful home.

What would Thoreau have thought about the world today? I often wonder that.