🏛 When the student becomes the teacher

An update on the humbling discomfort of beginning again

Greetings from Maryland. This post ran a year ago to mark the one-year anniversary of this Substack.1 It was one of the most-shared of the year, so I thought new subscribers might enjoy this peek into my “other” life. Writing it changed me in ways I’m still processing, so there’s a coda at the end.

I’m so grateful to have found this lovely community of writers and readers. Thank you, everyone, for your encouragement and support. May 2025 be full of blessings for you all.

“Most of us believe that teachers must know all. The wise Tao mentor knows that being aware of what is not known is important in order to begin to learn.”2

I had a grad student not too long ago who wasn’t catching on. It led to a falling-out between us that I still think about, years later. The students in that design studio come from different backgrounds and professions. They’ve turned their lives upside-down to become architects, giving up a career as a political scientist or engineer, a real estate agent, graphic designer, or biologist. I once had a veterinarian with his own practice. When I asked him how he decided to give all that up to start over as an architecture student, he said he loves the animals, it’s the owners he can’t stand. I thought (but didn’t say), Honey, wait till you meet clients.

Starting over is exciting and excruciating. Humbling. During my Fiction MFA program, I was teaching this same design studio and had the realization: my students are about as advanced in architecture (which is to say, not) as I am in fiction writing. And here I’d been hoping that years in a creative field could somehow vault me ahead. But of course, it doesn’t work that way. Improvement takes time and diligence; there are no shortcuts.3

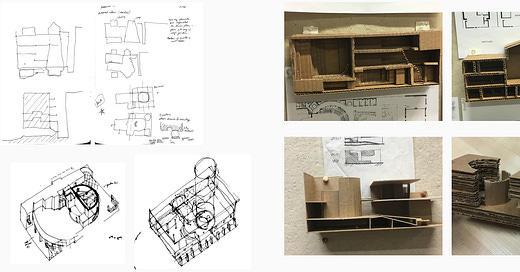

My goal for my students in Design Studio II is modest but demanding. They need to improve their spatial thinking skills. Working with structure and space is the foundation of all architectural design. We use spatial drawings to communicate abstract ideas to others. The semester includes visualizing space by studying precedents; representing spatial ideas with drawings, diagrams and physical models; reading theory about spatial thinking; and iterating their ideas many times over.

I emphasize that design is a patient search, that their first ideas can always be improved upon. I encourage them to imitate, adapt, and transform precedent, to absorb the DNA of great work. Their own unique ideas will only be legible once they’ve learned basic vocabulary and grammar. Learning by imitation: it’s what we do as humans, no matter the medium. Language, music, art, literature, dance, acting. Architecture is no exception.4

Leaving a successful career to begin again is rough psychological terrain. It’s not unusual for some students, especially those with a literary or philosophical background, to struggle with spatial thinking and representation. No shame; it’s a language of itself, a learned skill that takes time and practice. When I advised a couple of students one semester to consider taking an additional design studio in the summer for their benefit, one of them took the suggestion as a personal affront. How dare I suggest they need remedial work, when it’s my job to teach them, now? We managed to reach a détente and finish the semester, but they never trusted me again.

In the end, their course evaluation was searingly negative and personal, the worst by far that I’ve ever received.5 They said I was unfairly favoring some students over others. That I was incompetent, expecting another professor to do the job that I couldn’t. That I made them feel unwelcome. At first, I wrote it off as projection of their own doubts about the wisdom of choosing architecture school. Or maybe they had a chip on their shoulder, and I was their scapegoat for all things wrong with our culture.

Evaluations on both sides of this relationship can seem frustratingly subjective. Some architecture students are better able, innately, to grasp our lessons. That doesn’t mean others shouldn’t continue. There’s time for skills and talents to emerge, during grad school and out in practice. This student had been in architecture for all of four months, but given feedback by an experienced professor they chose to take it personally and push back with You’re wrong about me.

After many years at this, I know what students need to learn at this level and whether they are bringing the goods. I can recognize where a student is, relative to past and current peers, and benchmark where they are to guide them forward. It’s natural for a student to fall back on what they know, but especially at the early stages, if they focus on verbal descriptions of ideas but fail to produce visual representations of those ideas, they have a ways to go. (Don’t we all?)

Writers say the work must be on the page. Architects say it must be on the wall. Ideas are cheap if they can’t be represented with an architectural vocabulary of form and structure and space. Spatial drawings and diagrams are the tools, not fancy banter. Images, not words. Otherwise, it’s nothing but “talkitecture.”

When a student feels invalidated by criticism or believes their identity is threatened by pointed feedback, they can’t learn. Creativity shuts down. Fight/flight smothers creativity. All I can do is reassure them that others have been in the same situation and to trust the process. But this student didn’t trust me or the process. They were certain that I didn’t appreciate their unique genius. That I didn’t see them.

My own architecture school experience was a weeding-out. On our first day, one hundred of us sat in the auditorium, excited and nervous and clueless. We were told to look around, that half of us would be gone by graduation.6 Those days are no more, thankfully. Our students are like customers with expectations to be met. It’s our job to get them through, to equip them to succeed. So when a student feels unvalued, unseen, unwelcome, I’m left asking: what could I have done differently?

You can’t learn from someone you don’t trust. I’m disappointed in myself that I couldn’t repair that trust, that I didn’t reach that student during the months I had with them. I failed to teach them what they needed to learn.

It’s humbling to be reminded that mentoring is a mirror, a two-way street. As much as I want my student to learn, I recognize that this is my lesson. In the Taoist spirit that this student is my teacher, I can ask, What is my lesson here?

Where do I lack confidence? Where is my expertise lacking? Where do I feel unwelcome?

Simply asking these questions eases my mind. It increases my compassion for this student and for myself. I hate feeling like an outsider, and I hate that I contributed to them feeling that way.

“It matters not what we try to think or carry out; what matters is that once we begin we must never lose heart until the task is completed.”7

It’s not unusual for students to approach education as their chance to prove themselves, to shine and show off what they know. I’m not immune from this culturally installed mindset, but it gets in the way. The drive to stand out clouds curiosity. Over-identifying with prior expertise hinders learning something novel.

As I prepare for the upcoming semester of Design Studio II, I’ll try to remember that I have as much to learn as my students. They’re paying a lot of tuition to learn from an expert, so I won’t burden them with my secret: I am as empty a vessel as they are.

Coda

Looks like I have two things to add, one as a fancy college professor and one as a maniacal fan of an NFL team. Bear with me; I think they dovetail right at the end.

Thing 1. I love fall semester because I get to teach a really difficult advanced studio with three other colleagues who are as passionate and committed to the students as I am. This particular studio is sometimes referred to as a boot camp. The learning curve is laughably steep, and every year, the students meet and surpass expectations. The amount that they learn and apply is astounding.

I love that my colleagues bring complementary experiences and intelligence to our team. Together, we are a force. And, together, we helped our grad students face and overcome serious challenges. Their privacy prevents me from telling detailed stories, but I can say that I witnessed many acts of kindness beyond their expert mentorship, and came away tired but inspired.

Thing 2. My husband and I are watching a docu-series called “Hard Knocks,” which follows the four teams in the AFC East: Cincinnati Bengals, Pittsburgh Steelers, Cleveland Browns, and, of course, Baltimore Ravens.8 I’m fascinated by the inside look at training, family life, travel, community outreach, strategy sessions, film analysis, game-day prep, and interviews with key players. And you can’t argue with Liev Schreiber’s voiceover work.9

The pep talks are by far the most myth-busting part. Big guys sprawl in over-lit auditoriums and classrooms, taking notes on tablets, listening to coaches talk to power point slides about learning from failure and working together. On the sidelines, coaches pepper the guys with affirmations: great run, way to get it, stay focused. It’s so . . . basic. So human. Under all those muscles, all that gear and athleticism, they’re just people. People with egos and hearts and psyches as fragile as their bodies.

. . . and here’s the dovetail. . . I don’t know why this amuses me so much (it’s adorable), but as a teacher, I appreciate the reminder that anyone who seeks to perform at any level needs mentors and encouragement. Needs supportive peers and teamwork and constant reminders that they can do better. We all need each other. A little care and compassion go a long way.

Homecoming donates 30% of paid subscriptions to a different worthy environmental cause each season. So far, paid subscriptions have supported the Indigenous Environmental Network, the Old Growth Forest Network, and the Center for Humans and Nature. Track past and current recipients here.

Homecoming started 2024 with 400 subscribers and set an audacious goal to reach 1,000 by year’s end, which we reached on September 10th. We ended 2024 with 1,296 subscribers. 💚

Chungliang Al Huang and Jerry Lynch, Mentoring: The TAO of Giving and Receiving Wisdom, p.29.

They say architecture is an old man’s profession, in that it requires decades of practice to do your best work. I can honestly say, after trying both, that writing is harder.

I have a soft spot for the age-old practice of copying the “old masters” in art galleries, such as the National Gallery in D.C. Here’s an article about other programs.

You may wonder how I could discern a specific student’s responses from an anonymous survey. Trust me, it was obvious.

And that proved to be true.

Chungliang Al Huang and Jerry Lynch, Mentoring: The TAO of Giving and Receiving Wisdom, p.73.

I’m well aware that American football is seen as violent and rife with corruption and exploitation. It’s also an incredible game played by some of the most gifted, hard-working athletes on the planet. Two things can be true, there, I said it.

"anyone who seeks to perform at any level needs mentors and encouragement" - this is so true, especially for writers who are new to sharing their work. Receiving a kind word or even just a "like" on a piece that you have shared with the world, leaving the writer open and vulnerable, goes such a long way. Loved your essay and the parallels between writing and architecture - both involve building something out of just a few ideas.

You sound like an amazing teacher, Julie. And trust is so fragile...It must be so challenging to earn it from all of your students.

Congratulations on your Substack anniversary!