“The Future of Nature” is an Earth Day community writing project for fiction writers to explore the human-nature relationship in a short story or poem. It was organized by and me, and supported with brilliant advice from scientists and . The story you’re about to read is from this project. You can find all the stories as a special Disruption edition, with thanks to publisher .

For those of you reading my novel, FLUX, being serialized here, you may recognize a familiar character . . . who happens to be the great-grandmother of this story’s main character. Hope it’s not too much of a spoiler for the novel ~ !! 😉

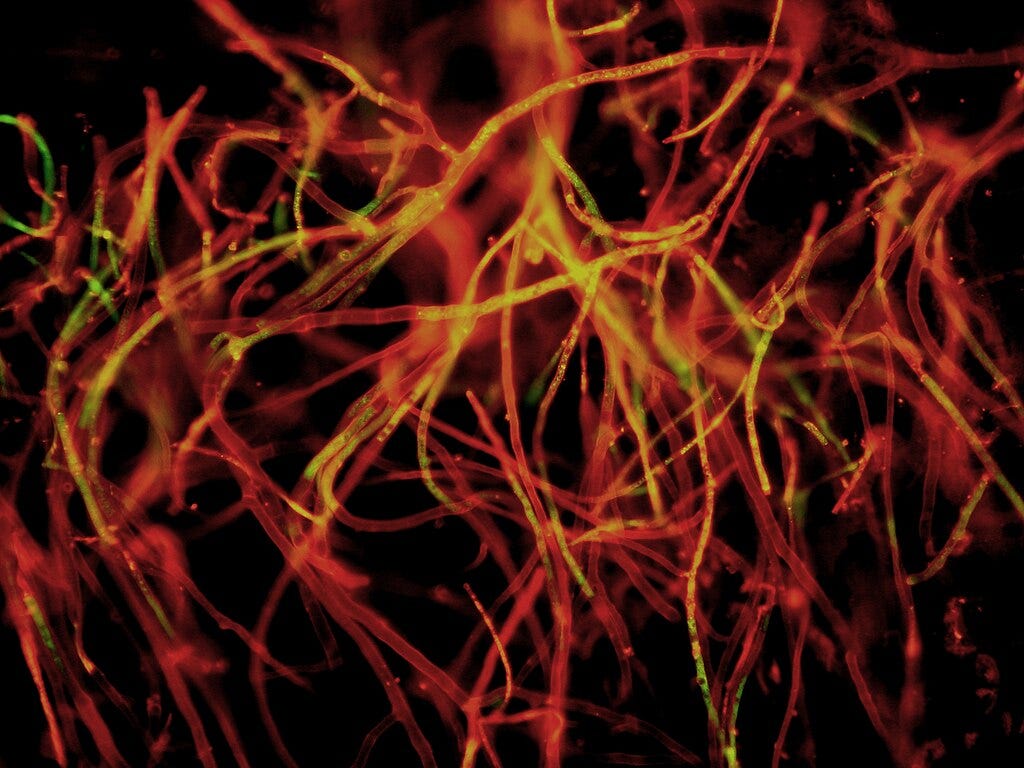

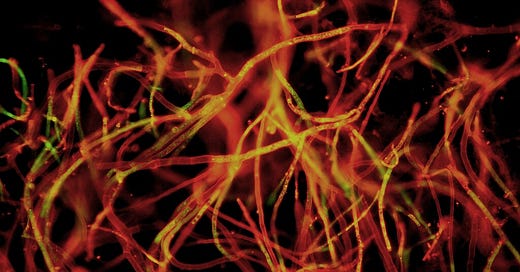

On the day after her miscarriage, Anna hikes the old growth forest for hours of silent contemplation. She pours her grief through her hands into the cool, damp, grainy earth. Her sorrow touches the ghostly filaments of mycelium to be held by the forest entire. Anna trusts an organism that first colonized land over a billion years ago and partnered with plants to entice them ashore seven hundred million years ago. That alliance evolved into animals and, in due course, her great-grandmother Grace; her grandmother Leonora; her mother, Serafina; herself; and the daughter who will join her someday.

Anna’s grandmother, Leonora Butler, was a lawyer during the time of Awakening and Reconciliation, after the time of Misery and Exile burned out in worldwide economic chaos, human suffering, and creative renewal. Villages, towns, landscapes had been abandoned. Banks had collapsed. Money wallowed in irrelevance. Finance bros cast aside zeros and ones, and turned instead to farming, building, and storytelling.

As a law student in North America, Anna’s grandmother Leonora Butler studied the 2032 case, Campbell v. Delancey, which stripped corporations of their nonsensical personhood. She went on to win two groundbreaking land rights cases before the World Court, in 2048 and 2051. Three more cases followed in the 2060s and 2070s, granting personhood to rivers, bays, forests, and mountains.

To Anna, the earth is a vast banquet with mycelium as the fork, the spoon, the platter and the stomach. People are the fruiting bodies of a living, connecting, ever-renewing network of intelligence. The garnish, if you will. The mushrooms.

Fungi encourage Anna to leave the center of things, to seek out edges. One cool October day during the rainy season, Anna mountain-bikes into the National Park. She climbs in a misty rain through the old-growth forest on a narrow, little-used trail thick with needles and bark chips. Fat columns of trees—Douglas Fir, Western Red Cedar, Sitka Spruce, Western Hemlock—tower skyward. Giant sword ferns, sorrel, and carpets of moss blanket the forest floor. The trail curves along a gray rock wall and narrows to a hint. She pushes her bike the last half mile.

This is one of my favorite spots in the world, she says to the trees. A hidden treasure. And there’s the Matsutake fungus she seeks. Hello, friend, Anna says. She scrambles down the slope. You’re here, she says, stooping low. Her voice rings with the delight of discovery.

The time of Misery and Exile felt like always. People were anxious and angry. Most believed everything the suffering and injustice and plunder was inevitable. That all would go on, unchecked, forever. That everything was, simply, the Way Things Are. The effort to keep believing in such a fate, to ignore breakdown and ruin, demanded much of them. People exchanged belonging for entitlement. In their exile, they

amassed,

ignored,

imprisoned,

lied,

lynched,

migrated,

mined,

occupied,

overheated,

orbited,

regulated,

rocketed,

impoverished,

impregnated,

birthed,

buried, and

mourned.

Comfortable, well-sheltered people predicted apocalypse if “those others” didn’t adopt earth-friendly, “natural” alternatives. Some, including Anna’s great-grandmother Grace, became irritable and judgmental; others turned to religion and the Rapture. Some made and binged zombie shows and post-apocalyptic porn.

Hopeful alternatives during the time of Misery and Exile were considered irrelevant indulgences. Organic farming, cooperative ownership, straw and mud buildings, and consensus governance lingered the edges, alongside permaculture and biodynamics.

The toddler’s tantrum of entitlement and blindness finally exhausted itself. When the market for natural gas collapsed, wells closed one by one. Leonora Butler and her daughter Serafina and their friends and neighbors planted trees on the barren well sites. They seeded Bjerkandera adusta, Grifola frondosa, Pleurotus ostreatus, and Trametes versicolor, among other mycelium to nourish and companion the fledgling forests.

Within a few feet, Anna finds another bone-white dome of Tricholoma Matsutake, nestled like an Easter egg among tree roots, bark, needles, and infant tree sprouts. It’s nibbled along one edge. She leaves it for the animals.

You’ve found the vein, the Grandmother Spruce says. Anna works her fingers into the inky sweet loam to coax another mushroom out. After a brief struggle, it pops off and lands beside her boot.

Anna scoops a handful of soil that smells of rot and time and life. It contains a miniature world of fungi, bacteria, and protozoa—more beings than the entire census of plants and vertebrates in all North America.

Encouraged by a cousin Cedar, she continues to explore and forage. The light is flat and green. The air is sweet and moist, bright with patient growing. Spiced with the intimate, connected generosity of beings far older than she.

The trees breathe. The ferns breathe. The fungus and the birds breathe. The soil breathes. Anna breathes.

She places her palm on the craggy, moss-spangled bark to greet a cousin Hemlock. She takes their life into her lungs, her body, her blood, her brain. She closes her eyes to feel the Hemlock’s slow unfolding. The exchange of carbon among the hidden roots beneath her feet. The exchange of nitrogen and phosphorus with her cousin’s neighbors, the sharing of water and defense signals and hormones, each to each in the language of trees. The omnipresent orchestration of the mycorrhizal network weaving ghostly hairlike threads among the roots of every plant. Hundreds of miles of mycorrhizal networks beneath her feet.

Anna lies on her back to gaze up at the giant, bark-crusted columns rising to spriggles of green at their crowns, impossibly far away and backlit by sky. Time circles and swirls. These trees have stood for hundreds and thousands of years, and now they confirm what she has already felt. She is pregnant again. To be here, in this place, is to be in the embrace of centuries, of a wisdom determined to continue.

During the difficult, chaotic, rapid transition to the Awakening and Reconciliation, people found new teachers: waterfall, limestone outcrop, moss, and maple, red-tailed hawk, cumulus, oak sapling, white-footed mouse, bullfrog, blueberry, flicker, bog turtle. And, the greatest sage of all, mycelium.

Scientists and artists, healers and engineers discovered that anything is possible when it came to mycelium, the earth’s oldest living organism. Anna’s great-grandmother Grace dedicated years of scientific study of the healing properties of Agarikon and Cordyceps fungus. She also experimented with the mycoremediation of anti-life bullies like industrial chemicals and long-chain hydrocarbons.

On the barren, abandoned well pads, where Anna’s ancestors lovingly tended the trees and fungus, a mysterious process unfolded. As the fungi grew and bloomed, they feasted, disassembled, unlocked, sequestered, transformed, and renewed. Through a reaction of fracking chemicals1 and methane lingering in the soil and water, the mycelial network recruited bacteria and plants to form a mutagenic neurotoxin. When caretakers pruned and mulched and watered the trees, they absorbed bits of the mycotoxin through their skin. They carried home the light scent of toasted walnuts on their clothes.

The toxin affected them in odd ways. Leonora wept at the sunrise as early morning light sparkled gold across resting fields. Her old uncle painted fat peonies preening among tight ant-covered buds. The toxin eased painful memories, rewrote DNA, released generational trauma.

While the fungi broke down and rendered harmless many contaminants on the now- healing well sites, they also accumulated heavy metals and could not be eaten safely. Anna’s mother Serafina had the brilliant idea to grow the mycelium for fiber, to be made into clothing. People could wear the beneficial mycotoxin close to their skin.

Mycofashion started small and grew through networks to every continent. Before long, the fungal clothing worked its magic. People convened truth and reconciliation circles. They returned land that was not theirs. They made restitutions. They unlearned and listened and respected and renewed their kinships. They rebuilt relationships,

closed coal plants,

dismantled incinerators,

ceased mining,

grounded bombers,

gave tribute, and

declared peace.

They replanted,

restored,

released,

wondered,

welcomed,

listened,

laughed,

cried,

created,

accepted,

enjoyed,

nurtured,

tended,

surrendered, and, at long last, once again, they

belonged.

One day in her fourth month of pregnancy, Anna will hike the National Park in search of Agarikon, Fomitopsis officinalis. The mushroom is small, about eight inches long, growing in the seam between the bare wood and bark of a forty-foot standing dead Hemlock. From a distance, the pale orange-pink growth rings and pearly globe give it the appearance of a whelk shell hanging upside down. Anna will admire the tiny droplets of water gathered on its curved white bottom. These will concentrate medicinal compounds, the fungus will whisper to her.

Anna will ask permission and the Agarikon will consent. I will take only a small piece, Anna will say, so you can heal. She’ll make a tiny incision into the underside to collect a thumbnail-sized sample.

She’ll slip her feet out of her boots and lie on her back on the mossy breathing earth. She will turn her head to bring her right ear close to the humming ground and pour everything out that ear—all her doubt and her longing, all confusion and worry, every expectation and resentment. Her suffering will drain away into the waiting earth.

With closed eyes, she will feel the rising sun warm her cheek, her nose, her chin with a golden whisper. A promise.

With a clear heart, Anna will turn her head to bring her left ear near the ground. The moss will tickle her neck and jaw. She may sneeze. She may whisper, Good morning. She may laugh.

Then, with the sun stroking her cheek, Anna will quiet and she will listen. As her muscles surrender, her body will feel held, every point of contact a prayer, and a reverent welcome.

On that day in her fourth month, the message will be simple—as it always is. Let my love shine through your body. My wisdom through your hands and words.

Her tears will leak over the bridge of her nose into the speaking earth. Spontaneous, unchecked offering of deepest humility and gratitude. My long wait is almost over, she will breathe. Relief will puddle in her limbs.

Oh, my dear one, the earth will say into Anna’s trusting body. Everything is always only beginning.

The world’s largest organism lives in a remote place in North America. The honey mushroom, Armillaria ostoyae, feasts on living trees and sprawls via mycelial network over four square miles (2.6 square kilometers) of mountain. Some say it’s 2,400 years old. Some say it’s been living and growing for at least 8,600 years.

Anna will arrive with her baby daughter for her naming ceremony. The fungus won’t be fruiting, but she will find the white fuzz of mycelial mats near the bases of Ponderosa pines and Sitka spruce. Telltale dark shoestrings of fungal rhizomorphs snaking from beneath the bark, over the roots and down into the soil, carrying their enzymatic language far and wide. The mycorrhizal network extends ten feet down into the soil and travels horizontally between hosts. Armillaria ostoyae is a very slow eater.

Anna will pitch her tent to spend a night with baby Amelia (a very fast eater) in the presence of the enormous being. For weeks after, they will dream of hawks, lightning storms, and blue whales.

Each season, we donate 30% of paid subscriptions to a worthy environmental cause. This season, it’s Women's Earth and Climate Action Network (WECAN) International. For The Earth And All Generations - Women Are Rising For Climate Justice & Community-Led Solutions. Track past and current recipients here.

What do you think? Can mycelium save us? I always love to hear from readers. Please share this story with others by restacking on Notes, via the Substack app. Thanks!

Even decades after fracking’s many violations, the chemicals persist: benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, xylene, tetrachloroethylene, ethylene glycol, propylene glycol, ethanol, butanol, propanol, chloroform, barium, sodium strontium, cadmium, thallium, chloromethane, bromodichloromethane, trichlorofluoromethane, cobalt, mercury, lead, arsenics, etc.

This is ecstatic Julie. I want to reach into the future and thank Anna’s great-grandmother for “granting personhood to rivers, bays, forests, and mountains.” I want to close my eyes tonight and dream about this time, believing in its possibility. And I love how the mycotoxin plays a central role in shifting humanity’s consciousness! Like Terence McKenna’s Stoned Ape Hypothesis that suggests that the consumption of psilocybin mushrooms by early hominins played a crucial role in the rapid evolution of human consciousness, including the development of language, symbolic thinking, and self-awareness.

I love imagining these ancient spores and mycelia having an intelligence and strategy far more sophisticated than our own, guiding us toward a more harmonious future.

I love the idea of mycelium saving us. I also loved the pace of your writing in this. It read like music.