Hello, everyone! And a special welcome to new subscribers. You’re in the right place essays on architecture, teaching, or encounters with the sublime; bi-monthly interviews with nature writers and NatureStack, an occasional journal Substack’s best nature writing. Wherever you are on this path — if you’re brimming with wonder or weary with grief — you belong here.

The days are growing longer here in the Northern Hemisphere. Perfect time to dive into a novel like FLUX. . . Start here at the T.O.C.

⬅️ Previous chapter

Early October 2009

Grace’s Corolla needs a $1200 repair. Even if she had the money, the mechanic assures her the car’s not worth that much. She’s supposed to visit her mother today, but the bus takes an hour. If it’s on schedule, which it often isn’t. Time is far too precious for that nonsense. Out of desperation, she asks Ned for a ride.

Francesca is on medical leave from the middle school. She tolerated the chemo well, until she didn’t. Between nausea and brain fog, she can’t manage the boisterous, hormonal kids.

Grace has been spending the night more often. Last time she got there, her mother had gone out and left her cell phone on the kitchen table. Grace called Francesca’s friends, fighting panic. Forty minutes later, her mother returned. She’d gone to Best Buy to buy a phone for her bedroom, where she spends more and more time. It didn’t occur to her that the cell phone would work there.

“Ma, you shouldn’t be driving,” Grace had said.

“Don’t treat me like a child,” was the answer. End of discussion.

She hasn’t seen Ned since fall semester began. No time for the farmer’s market. Their crab date never materialized (her fault). He texts links to his articles and updates on the Orioles’ abysmal record. Not that she cares, but thanks to him, she knows they ended September losing twelve in a row. Ned’s relief that they won their last four games was matched only by hers that she managed to resist his every invitation to go to the ballpark.

“Hey, dummy.” His odd greeting is accompanied by a wide smile, so she decides not to take it literally.

He's in a jaunty mood. Their outing may be an adventure to him, but for her it’s an obligatory visit to a sick old woman. A sick old woman who happens to be her mother. She instantly regrets asking him. How could she not have thought through the horror of Ned and her mother in conversation?

His dark blue Volvo wagon is old but well cared-for. It has the sharp dusty smell of vinyl surfaces so depressed from years of merciless sunlight that not even Ned’s devoted buffing with Armor-All can cheer them up. The backseat is covered with copies of the Sun, but the car is otherwise tidy.

Grace studies his profile as he slaloms down St. Paul Street, dodging double-parked cars, stopped buses, and slow drivers, working the clutch and stick shift hard.

He’s clean-shaven. All the times she saw him at the market, he had day-old growth. She’s not sure which she prefers. His khakis are pressed with a center crease, his sweater forest green cable-knit over a button-down, his loafers polished. He’s not wearing his trademark frayed Orioles cap. Maybe he retires it after the season’s over.

“We could stop by a corner store, pick up a chicken box and a half and half,” he says.

Grace shakes her head. “No idea what you just said, but I’m good.”

“Half and half? It’s iced tea and lemonade.” He gestures towards the upcoming intersection. “Last chance before we get on the JFX. Nadine’s is the best place in this part of the city.”

“No thanks.” They pass a storefront advertising LAKE TROUT in tall red letters. She’s never dared to venture into one of Baltimore’s corner stores.

He points to the CD holder strapped to her visor. “Want to choose some music?”

She tugs on one, which turns out to be the Official Baltimore Club Classics vol.5. “What’s this?”

“Oh, you’re in for a treat,” he says, and slips it into the player.

The car fills with a snappy percussive rhythm under a jaunty roll call of Baltimore neighborhoods. “Greenmount in the house. . . Harford Road in the house. . .” Grace can’t listen to it without swaying in the seat.

“Right?” Ned says. “Club Music will lift any mood. Pure joy.”

“Never heard it before, but yeah, it has an effect.”

“Hey, what are you doing next weekend?” he asks.

“Working.”

“How do you know already?”

“Is that meant to be funny?”

He glances over with a half-smile. “I’ve never met someone who plans a week ahead for overtime. It’s meant to be a last-minute thing. Like when my editor needs another rewrite before I can go to the Orioles game, that sort of thing.”

Grace snorts. “Trust me, plenty of people work weekends.”

“Sure, doctors and baristas.”

“And grocery clerks, nurses, taxi drivers, cops—”

He raises both hands briefly off the steering wheel in mock surrender. “Okay, okay. You made your point.”

“Don’t do that.”

He looks over at her. “Do what?”

“Eyes on the road, geez.” At least with the bus she knows she’ll get there in one piece.

“Oh, you don’t like my driving?” He smiles. “Or is it the lack of control? I was thinking we could go to a club, do a little dancing.”

“Pass.”

At a red light, he studies her. “It’s good to take a break now and then. Rest your brain. Studies show—”

“Nope. Not gonna happen.”

“Life’s too short, Grace. You can’t work all the time.”

“Watch me.”

“Okay, then, what do you enjoy doing outside your lab?”

“Besides sleeping? I like to fly.”

“Where do you like to go?”

“No, I mean, piloting a glider. I used to be obsessed but when things got too busy, I stopped cold turkey. I’ve started up again. I get out now and then.”

“I knew you were a badass, but hang gliding? It’s so dangerous.” He zips between a dump truck and a stopped car with inches to spare.

“No more so than your driving,” she says. “Nothing in life is risk-free.”

Grace is fastidious with every safety protocol. Only once has she had to deploy her reserve parachute, an experience she is not keen to repeat. The mercurial wind shift was unavoidable, but she ended up with three broken ribs and a repair bill she could ill afford.

“If Hélène ever wanted to do it, that’s an easy hell no.”

“My father said the same. I just forged his signature and went anyway. He couldn’t stop me.”

“Geez, you must’ve been a nightmare daughter.”

“He was a nightmare father, so, we were well matched.”

“How old were you?”

“Fifteen.”

Ned whistles low. “Did he ever come watch you flying?”

“No way.”

“If it were me, I’d—”

“What? Forbid your daughter? Lock her in her room?”

“I was gonna say, I’d go watch her.”

Something twangs in Grace’s chest. “You must be a great dad.”

“And you must’ve been a handful.”

“Not really. I was mostly . . . quiet.”

“Quiet but subversive?”

Grace laughs. “Sometimes. Maybe not enough.”

The road to Curtis Bay ends in a T, facing a double billboard. On the left, recruiting for the military. On the right, parenting tips and a hotline. “Way to sum up a neighborhood,” she says.

After he turns right, she reads signs aloud.

“For Sale. $600 a month to own,” is hand-lettered on cardboard, hung from the porch column of a rowhouse.

“Hiring Drivers, Equal Opportunity Employer,” on a bright yellow banner pinned to a fence along the Curtis Avenue industrial buildings.

Curtis Bay is a miniature San Francisco, clinging to the hill between the Patapsco River’s harbors and the iconic water tower at its crest. The blocks-long brick warehouse that parallels the waterfront is a relic of shedding paint and broken windowpanes that prohibits water access. Cranes loom over coal stripped from Appalachian Mountains and poured into Stygian piles that are like holes cut from the silver water beyond.

“Food, Cold Drinks, ATM and Hall Rental,” Grace narrates from the American Legion Post.

Ned is so garrulous, she needs to set some ground rules. “This is a quick stop. See what errands she needs run, in and out. Don’t make me regret bringing you.”

“I brought you, remember?”

“You know what I mean.”

“You could borrow your mother’s car.”

“She needs it.”

“Thought you said she shouldn’t be driving.”

“She shouldn’t be, but. . . It’s not my place.”

“As her daughter? Whose place is it, then?” His question makes her chest ache.

“In case you’re gonna ask, I don’t have power of attorney. Yet.” The ache tightens into a cramp.

“It’s not good for a car to sit idle too long,” he says. “You’d be doing her a favor to exercise it.”

“It’s a car, not a horse.” The memory of her mother’s adage about gift horses makes her smile, then laugh. So absurd. But she took the advice and the money, didn’t she? Grace laughs and laughs. She can’t stop. Tears come, the emotion fills her body, darkens like a rain shower on a sunny day, and now she covers her face with her hands and crumples into herself sobbing.

The car slows to a stop. Ned’s hand on her back not moving. A warm, light weight.

“I’m s-sorry,” she gasps from her hiding place.

The hand moves across her shoulder blades, spreading calm kindness.

“We should go,” she whispers.

The hand rests. Grace rests.

“When you’re ready,” Ned says.

Grace isn’t familiar with the feeling of taking her time. Allowing her body to come to stillness. She could fall asleep. She’s never been so tired.

Once she sits up and dries her face with her sleeve, Ned pulls away from the curb to turn west, uphill from the waterfront.

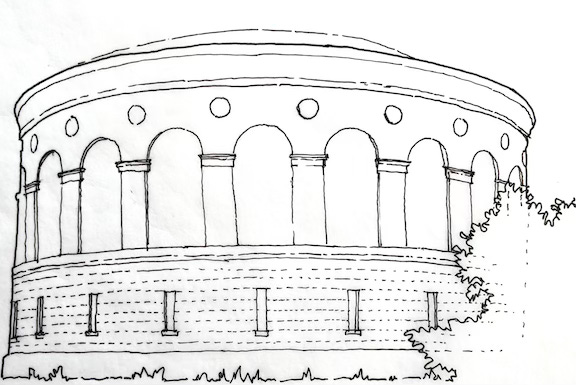

While Baltimore’s industrial past decomposes along the water, at the top of the hill sits a monumental round water tank beautified by Depression-era craftsmen. They laid twenty shades of tan and brown brick to form two dozen classical arches and topped it with a gleaming white dome. Now, under the tank’s watchful gaze grows a one-acre community garden.

Francesca looks thinner but ready for High Tea in a lavender pants suit, jewelry, and make-up. “Grace, dear, why didn’t you tell me you’re bringing a friend?” She pats her perfect hair and gazes at Ned like he’s the Gentleman Caller from The Glass Menagerie.

“Mom, this is Ned. He gave me ride. My car died.”

Ned extends his hand. “Very pleased to meet you, Dr. Evans. I’ve heard so much about you.” Grace hasn’t said more than a dozen words to him about her mother. From behind his back, he produces a package of Berger Cookies.

Francesca laughs like a schoolgirl and slips her frail, bony hand into his. “How thoughtful of you.”

“She doesn’t use Evans,” Grace says, taking the package. She hadn’t even noticed him carrying them. It takes all her will power not to head straight to the kitchen to devour one of the buttery, fudgy cookies.

Her mother waves her free hand, still clinging to Ned. “It’s fine. No one calls me doctor. It’s Francesca, please.”

“Really?” Grace asks. “You’re not Dr. Serra at school?”

“Heavens, no. My students call me Miss Francesca. It’s the Baltimore form of respect.”

Grace winces to recall the years of crushingly hard work to earn her PhD. She’s offended that her mother has given up so much. It’s like she’s living in witness protection.

When Ned releases her hand, she sways a little. “Let’s sit,” he says, gently steering her by the elbow to the flowered sofa.

“I’ll get drinks. Mom?” Grace calls from the kitchen doorway.

“I meant to make tea, but . . . Everything takes so long now.”

“How about Coke? Ned?”

Ned calls back, “I’m happy with anything.”

Grace brings a tray with the last two cans of Coke, three glasses, and a plate of the cookies. She pours them out and settles on the ottoman with a cookie—her second. Ned has kicked back in the plush easy chair. Her mother perches on the edge of her cushion.

“So,” Grace says. “How are you?”

Her mother pales. Ned shoots Grace a look, like Do better.

“Francesca, what’s new in the neighborhood?” he says.

The old woman brightens. “Mr. Collins? Across the street that way?” With some effort, she gestures over her left shoulder. “His cat was out all night prowling and yowling. Kept me up for hours.”

Grace is embarrassed. She sounds like an old lady at Bingo night, not a PhD mathematician.

“Oh, no,” Ned says. “That’s terrible. I could go speak to him, if you think he’s amenable? I’m sure he has no idea. He wouldn’t want you to lose sleep because of—”

“Sylvester.”

“His name is Sylvester?”

“No, the cat. The cat is Sylvester. Normally a real sweetheart.” She sips her Coke. “You know, I don’t know Mr. Collins’ first name. We’ve been neighbors for nearly ten years.”

Grace wonders if Collins calls her Miss Francesca too.

“Don’t worry. We’ll speak to him.” He gulps Coke. “This is a lovely home. You must be very comfortable here.”

“Oh, yes.” She glances at Grace with admiration. WELL DONE! might as well be flashing above her in pink and purple neon script. “I’ve been here fifteen years. A lot of changes, but you still meet folks who were born here and grew up playing ball up at the water tower.”

“Impressive. I’ve seen that tower from the water, but never this close. A real Baltimore icon. They don’t make ‘em like that anymore.”

“Yes. We’re proud of it.”

It stings that her mother is proud of a water tower and not her own daughter. “Mom, what errands do you need us to run?”

Ned meets Grace’s eyes, with a barely perceptible headshake. His disappointment stiffens her limbs. “Grace, did you tell your mother about that oven you built?”

What’s he up to with this charm offensive? It hits her that never, not once in her life, has she had to endure the ritual of meet-the-parents. One benefit of her miserable childhood at least. Not that Ned is her boyfriend. He gave her a ride, that’s all. And she’s a grown woman.

“An oven? What on earth?” Francesca smiles at Ned, her head tilted in anticipation of a good story.

Grace sighs. “I went to a farm near one of my study sites, to get them to sign a release for me to place equipment there.”

“Didn’t you have to take one of their workshops before they’d meet with you?” Ned asks.

Grace stares at him. “How’d you know that?”

“Barbara told me.” Ned pulls a cookie off the plate. “They built a domed pizza oven from clay and straw,” he says to Francesca.

“How wonderful! My father had one of those—”

“I doubt it—” Grace says. When did Barbara talk to Ned, and why didn’t she mention it?

“E vero,” Francesca says. “It was stone, plastered with mud. He made the best pizza in the whole world.” She glows with fond nostalgia.

Grace’s mother slips into Italian when confused or emotional or talking about food. This embellishment is new. It seems deliberate, like she’s trying to impress Ned.

“We could build one here,” Ned says. “In your backyard.” He gestures towards the rear of the house.

“Marvelous,” Francesca says. “What a generous offer. Would you really do that for me?”

“He’s kidding, Mom.”

He shakes his head. “I’m not. I’ve been dreaming ever since Barbara told me about it. My landlord said no. And my ex, don’t get me started. She lives in Homeland, one of Baltimore’s most uptight neighborhoods.” He drains his glass. “It’s settled then. Show us where you want it.”

Grace wants off this moving train. She should’ve taken the bus. A couple of hours is nothing compared to what he’s promising.

“It’s a lovely idea,” Francesca says. “You know what would be even better? Build it up at the garden. The kids would go crazy for a project like that. Could they help?”

“Absolutely. There were tons of kids playing in the mud at the farm, spraying hoses at everyone.” He couldn’t be more delighted if he’d been there himself. “Right, Grace? And you too?”

“When did you talk to Barbara?”

“I stopped by the lab last week, since I hadn’t heard from you in a while. You were up in Pennsylvania, so Barbara and I went out for lunch. I asked her to tell you hello.”

Grace and Barbara have been busy, missing each other lately. Maybe Barbara’s avoiding her on purpose? She has no right to gossip about her to Ned.

“Can you please go to the garden while you’re here?” Francesca asks.

Grace shakes her head. “Not today. Maybe next time.”

“Of course,” Ned says. “What do you need?”

Francesca looks between them, chooses Ned. “I volunteer there three or four days a week. Well, I used to. Now is their busiest time. But lately. . .” She lifts and drops both arms like dead weights. “Useless. There’s so much to harvest. They need all the help they can get.”

Ned agrees with enthusiasm. Grace wants to argue with him, but the grateful relief on her mother’s face stops her cold.

“Let’s make it quick, in and out,” she says as they trudge up the hill.

“Look at these stoops, everyone has such house pride,” Ned says. “I can’t believe I’ve never been to this neighborhood before.”

“Must be more crime to cover in the bad neighborhoods.”

“Every neighborhood has its challenges.” Ned stops to admire a bed of purple and hot-pink Asters. “Even the worst block is someone’s home.”

They arrive at the corner of Hickory and Prudence where five wood planks stretch between two teal-painted posts. The top one proclaims Hickory Street Garden in dark blue script against a bright orange background. The others announce the Herb Garden, School Garden, Orchard, and Outdoor Classroom in bright aqua, yellow, peach, and green lettering.

It looks deserted until a small, stout woman emerges from a shed carrying a stack of plastic tubs. She sets the tubs down, rubs her gloved hands on her slacks and approaches.

“May I help you?” Her expression skirts annoyance. The dark skin of her face is wrinkled, her head wrapped with a bright, patterned cloth. She could be forty or eighty.

Ned extends his hand, smiling broadly. “Ned Clark, with The Sun. This is Dr. Grace Evans.”

“You’re here to do a story? I wasn’t informed.” She checks her watch, frowning.

“No, no,” Grace says. “I’m Francesca Serra’s . . . daughter.” The word feels strange in her mouth.

The woman smiles wide, showing a gap in her front teeth. She reaches out with both arms. “Oh, dear Francesca. How is she? We’re so worried.”

Grace isn’t sure how to respond to the hands extending towards her. She settles on meeting them with hers. “She’s . . . okay. She, uh, sends her regards.”

The woman squeezes Grace’s hands. The gloves are worn and soft. “Come in, come in. I’m Evelyn. Your mother is an angel. We all love her so much. We’re just crushed.”

“Thanks. Um, she sent us to help out.”

“Isn’t that just like her?” Evelyn assesses Grace. “Oh, she talks about you all the time. So proud of you, her bright, beautiful daughter. I’m glad to finally meet you.”

Grace struggles to process the praise while Evelyn continues. “There’s plenty to do, that’s for sure. How long can you stay?”

“A good hour,” Ned offers. “Maybe longer, if you need us.”

Grace elbows him in the ribs and Evelyn smiles. “Careful, we’ll hold you to it.”

The garden is a pocket-sized version of Dragonfly Farm, complete with a gaggle of roaming chickens. There’s even a small pen with two friendly sheep. This humble garden, fed by city water from the monumental tank looming sunlit gold over them, probably produces cleaner food than a two-hundred-acre organic farm surrounded by methane extraction.

“Impressive you grow all this in such a small area,” Ned says.

“Oh, there’s nothing folks can’t do when they work together.” Evelyn narrates what’s growing: two kinds of squash, four of tomatoes, three of kale, nodding sunflowers, eggplant, beans, tall stalks of okra, a riot of flowers—red, orange, yellow, rose, purple. Shiitake mushrooms crowd gnarled oak logs. Hand-sized honeybaby squash spangle vines, masses of branch-veined Swiss chard wave from blood-red stalks, carrots hide beneath feather fronds, lace-eaten greens quiver above fat beets, purslane sprawls, chicory curls, frisée scraggles. Fresno, Anaheim, jalapeño, and habanero peppers glow green, orange, red. The leaves of the peach and cherry trees are turning shades of orange, red, bronze. Pink Lady apples hang ready for picking.

“Ten years ago, this was a vacant lot covered in trash,” Evelyn says. “A real rat resort. Bunch of us got together and cleaned it up. A local foundation loaned us tools, taught us the basics. Many of us take master gardening classes, your mother included. But anyone can pitch in and receive produce in return. The vets from the American Legion come on Fridays. Boy Scouts were here this morning.”

Another woman arrives while Grace, Ned, and Evelyn harvest kale and chard. She’s tall and slender, lighter-skinned than Evelyn, younger.

“Marianne, come say hi,” Evelyn calls. “She’s one of our certified Master Gardeners. And a beekeeper extraordinaire. Marianne, this is Grace, Francesca’s daughter.”

Stepping into this identity feels to Grace like opening night in a play without a single rehearsal. She has no idea how to be someone’s daughter. Someone who is known and beloved.

Marianne recruits Ned to help with the squash and eggplant. “How’s the composting business, Marianne?” Evelyn asks.

“Coming along.”

“Some of our high school students wanted to start a business, so Marianne helped them figure it out and launch it,” Evelyn explains.

“We got a grant from the city,” Marianne says. “The kids took a certification course, and our local bike shop here helped them rig up trailers. They bike around to collect food scraps from local restaurants.”

Evelyn hefts a tub full of greens. “When it’s ready, they’ll sell bagged compost to garden stores.”

Marianne smiles. “It’s called Water Tower Gold. The logo designed itself.”

“We started a college fund for the profits,” Evelyn says. “Anyone who works in the business can draw from it.”

“They just signed their first two restaurants, down the Inner Harbor.” Marianne points north. “Six miles.”

“That’s a bop,” says Evelyn. “Better them than me.”

Kids bike all that way to pick up food scraps? Not Grace’s students. They drive six blocks to school.

“This is a great story,” Ned says. “I’d like to come back here with one of our photographers. My editor would love this as a Sunday feature.”

Evelyn beams. “See? I knew I liked this guy.”

Marianne touches Grace’s sleeve. “I’m devastated by your mother’s diagnosis. We all visit her whenever we can. We bring groceries, meals, flowers from the garden. Catch her up on all the neighborhood gossip.”

“Her church friends started a phone tree,” Evelyn says. “You can sign up to go work a puzzle or just sit with her. Yesterday, we played dominoes.”

Grace’s eyes well with tears. An ache blooms in her throat. She turns away to pull a stalk of chard. “That’s . . . nice to hear,” she chokes out.

Evelyn squeezes her shoulder. “We wouldn’t have it any other way. She’s one of us.”

The chard is textured and weighty in Grace’s hands. The mulch dark and loamy. It steams a sweet-bitter smell of coffee and burnt toast. Grace surrenders to the kindness of the plants, which pull her to them.

The sun is low behind Grace and Ned as they return down the hill to Francesca’s house. Evelyn gave each of them a paper bag stuffed with produce, though Grace tried to refuse. Ned’s enthusiasm overruled her. “I’ll cook. You’ll love it.”

They find Francesca sitting in her tiny backyard, wrapped in a mint-green fleece blanket. “I love this time of day,” she says.

They join her to watch the sky shift from pink to violet to luminous indigo. To the east, a silhouetted cloud of starlings boils in a linear puff of smoke that divides and folds back in a dance of dense darks and lacy lights.

Grace stands, rapt, at the fence. She follows one bird and loses it as the billowing cloud streams over them: full immersion sound, waterfall flowing, trance storm of birds alive and free.

How can it be so effortless for you? So all-in? Grace whispers, electrified with wonder. How do you not collide? Do you ever get distracted or lose your way?

The birds roil over the houses as one organism, one shared mind.

What’s it like to be inside the dance?

“Grace, honey, who are you talking to?” Francesca’s voice startles her out of her reverie.

Grace turns. In the gloom, she can just make out their faces.

“Oh, you still do it,” her mother says.

“Do what?”

“Talk to them.”

She could deny it, but instead she stands there, exposed.

“I heard you, too,” Ned says. His voice is quiet in the dim light.

They all watch the birds turn, pivot, bank, dive, soar, spiral, circle, fold, flow. For joy, for protection, for survival. A cloud closing, a breath opening. A wave crashing on a shore. Billowing, boiling flux.

Next chapter ➡️

If you’re interested in environmental justice, here’s a recent article about research conducted by University of Maryland and the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health. They studied the adverse health effects of coal dust from the terminal pier at the foot of the Curtis Bay hillside. It links to the July 2025 published paper.

One of the best things about reading serial fiction on Substack is the community that gathers around. This is slow reading at its best. Twice a month, everyone experiences a new chapter and gets to weigh in on what’s happening in real time. When I’ve read stories this way, whether short fiction or whole novels, the interactions with both readers and authors is one of the most enjoyable aspects.

Each season, we donate 30% of paid subscriptions to a worthy environmental cause. This season, it’s Women's Earth and Climate Action Network (WECAN) International. For The Earth And All Generations - Women Are Rising For Climate Justice & Community-Led Solutions. Track past and current recipients here.

Aerial photo by Yazan Aboushi – from this site. Run by the Baltimore Compost Collective, the Filbert St. Gardens is a community project that was birthed out of an abandoned parking lot. Today it serves as a community sanctuary, where organic food is grown, local youth are employed, and educational workshops are offered to local residents.1

I believe this is my favorite chapter so far. There are many things to say about what is done well from a craft perspective.

This sentence hit hard, "Grace isn’t familiar with the feeling of taking her time." Ned, as a separate voice, "Do better" after an equal palpitations and the yin-yang gives this section such depth.

I'm still catching up..

I like this chapter very much, Julie. Grace's armour peeling away as she helps in the communal gardens, touching the soil, smelling it... the fresh produce, the community. Then the birds, the colours in the sky... all the things this beautiful planet gives us for free... this is why she does what she does.

Grace in a state of grace.

Her history with her mother won't just go away because of this day, but it's good to have these moments; I like Ned, bringing Grace to herself, giving her time, bridging the gaps.

I liked Grace at the beginning then not so much and now I like her again... she is complicated, complex.

Looking forward to reading the next chapter!