💡Every great building tells a story

From polished to primitive and back again at Aalto’s Villa Mairea

Besides marveling at the endless wonders of the natural world, sometimes I write about architecture.1 Today, I’m pleased to bring you a look at a building that delightfully satisfies both: Finnish architect Alvar Aalto’s Villa Mairea in Noormarkku, built 1938-1939.2 I had the dumb luck as a grad student of being assigned this building—one of Aalto’s finest—to study in depth. And two weeks ago, more luck landed me there in person.

This house cannot be over-hyped. As we pulled up, I gasped. It’s both stunning and familiar, lovingly detailed, with touches of stucco and glass, teak and pine and copper in all the right places. It’s always surprising to accompany my body and senses to a place I’ve studied and adored intellectually. This house has lived rent-free in my head for decades.

Often, my architectural crushes are bigger or smaller in real life than I imagine. The Pantheon in Rome is much larger, adding to the awe of stepping in from the bright busy piazza outside. Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater is intimate, with petite rooms (like FLW himself, it must be said—small but not at all modest).

The Villa Mairea, for whatever reason, is exactly as I expected. Set among pines in a forest, it feels rarified. Step into the entry hall and before you can even remove your shoes, you notice two Braque prints, a Picasso drawing and a Calder mobile. Well, okay. Game on.

This is a house of stories. First, we’ll look at its hidden meanings as a complete work of art, and then get into the fascinating client-owner, Maire Gullichsen, and her relationship with the Aaltos.

Reciprocity

In my very first semester of architecture school, one of our professors asked a question that I still think about. I’ve repeated it to my students countless times, but I can’t recall how it landed with me at the time. It probably confused me. I was confused a lot back then.3 The question is this:

What does it mean to make a mark upon the land?

At the time, and for many years after, I considered this from the obvious human-centric perspective: as a maker, a designer. Within this question is a sense of responsibility, yes, but it tends toward the transactional. It imagines a one-way relationship. We make a mark. Upon the land. There’s no room for the land to make its mark upon us. At least explicitly, there’s no reciprocity. Can this question be revised? Let’s try.

What does the land experience when we make our mark upon her? Ewww. That’s creepy, objectifying and transactional. No no no no. We can do better!

What’s possible when we collaborate and co-create with a place?

Let’s keep this question in mind as we consider the Villa Mairea.

A clearing in a forest

“The fundamental theme underlying the design of the Villa Mairea is the Enlightenment debate which, since first initiated between Rousseau and Voltaire, has not ceased to animate western thought: the debate between nature and civilization; between rusticity and the man-made; between the country and the city; between the primitive shed and civil habitat.”4

As I’ve written before, responsible architecture is always about something. We can study a building’s position, form, geometry, composition, details and materiality to decipher specific cultural attitudes and meanings. There is no more potent potential for meaning than the relationship between a building and its site. This question has been at the poetic heart of architectural ideas since antiquity.5

When analyzing Aalto’s Villa Mairea as a grad student, I was guided by our professor’s questions, below. These may seem artificial, stilted and oppositional. But such abstraction is a means to an end—to discover hidden meanings. When I bring curiosity and openness to investigations like this, I’m always rewarded with new insights.

Is the landscape hierarchically more important than the building or vice versa?

Does nature impose order, or is human order primary?

Does a duality exist between the human and the natural or is there a continuity?

To what extent is an interior complete in and of itself and to what extent is it continuous with the landscape outside? Does this represent an attitude about the making, or inhabiting, of landscape?

Is the human realm or the landscape seen as fragmentary or complete? Are they mutually dependent?

The Aaltos and their client were too clever to be satisfied with mere opposition of “nature and civilization.” Instead, this house can be read as a time-line, a history of settling in a place, of the development of artifice, from primitive to polished, from rustic to industrial.

Since it was designed to be a respite from the demands of urban life, that timeline may also, perhaps more meaningfully, be read in reverse. To leave the demands of bustling city life behind and step fully into the forest, one must undergo a certain transformation. As such a portal, the house works its magic on the tired, distracted industrialist. Each rattan-wrapped column she touches, each curved form, each framed view of the pines, is like shedding layers—coats, boots, hats, scarves, identities. Until, at the back of the garden, she enters the oh-so-rustic sauna to be fully cleansed and revived.

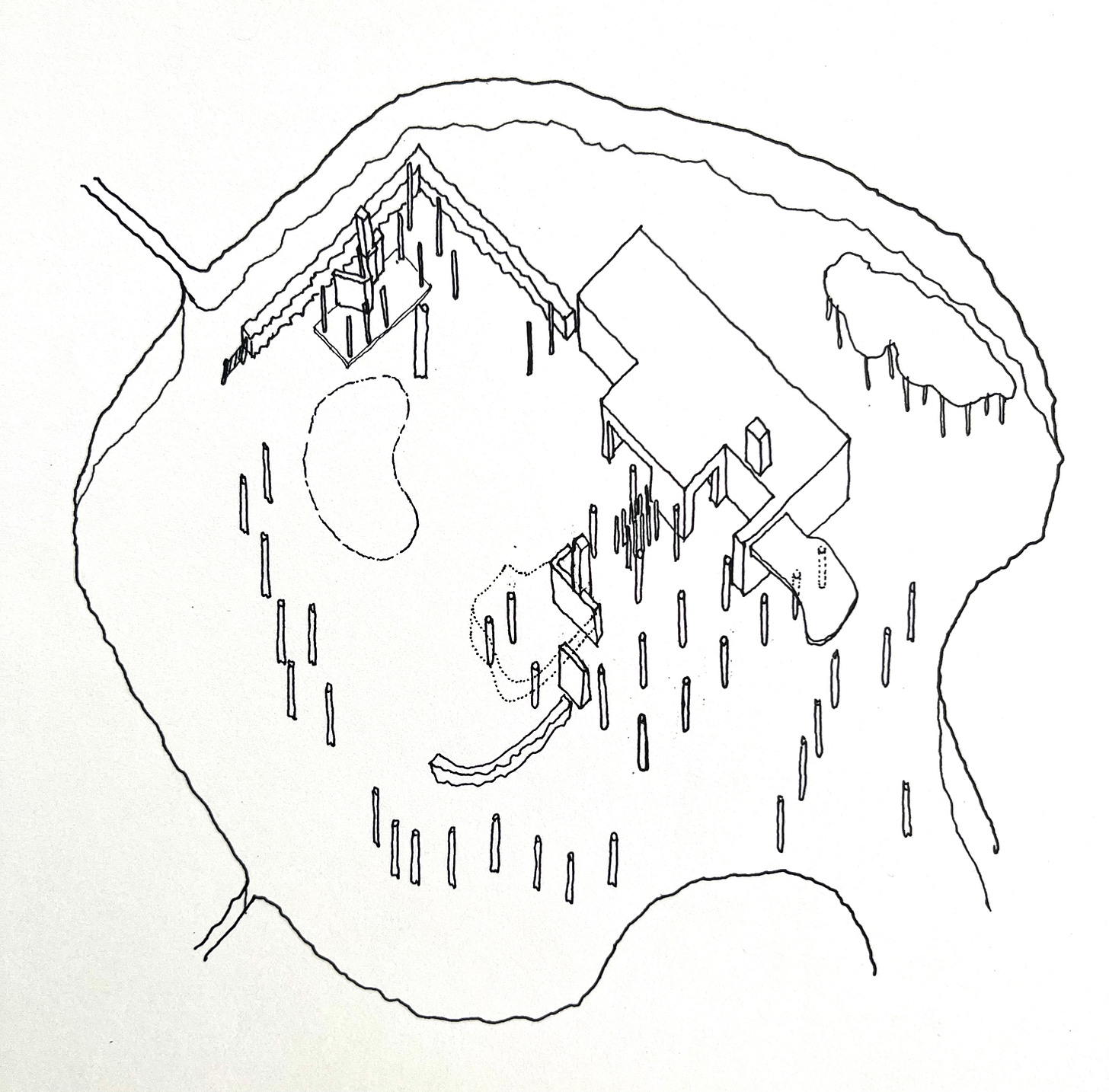

This video takes you through the house and touches on the evidence of this idea throughout. After the photos, I’ve included diagrams to illustrate the way I deciphered the house in my grad-school analysis.

Client matters

Our tour was limited to the first-floor rooms because the house is still used by the grandchildren and great-grandchildren as a holiday getaway.6 The client’s vision was a house full of art that works for a real family’s real life. Oh, and the house itself must be a total work of art.7 Maire was so serious about her charge that Aalto’s early schemes separating the living rooms from the art gallery were abandoned. She insisted on connecting everyday life with art.

The Gullichsens and Aaltos were friends before this commission. In 1935, the art historian, critic and writer Nils-Gustav Hahl introduced Aino and Alvar Aalto to Maire Gullichsen. Together, they formed the company Artek to produce and distribute the Aaltos’ furniture and glassware.8 Bear in mind, Maire is 28 at this point and an heiress who needs not work. Yet she was a driving force at Artek as chair of the board of directors for 36 years, including a 2-year stint as managing director in the 1950s.9

Maire Ahlström Gullichsen was born 1907 into Finland’s largest industrial dynasty. She studied painting in Paris at age 17, then went on to collect Degas, Bracques, Piicasso, Calder, Gris, Matisse, Gauguin, Arp, Leger and others.10 When her father died suddenly in 1931, Maire’s husband Harry was tapped to lead Ahlström. He was all of 29.

A vivid illustration of her devotion to being surrounded by functional beauty is the celluloid, leather and polished chrome PH Grand Piano, designed in 1930 by Danish architect and writer Poul Henningsen. Henningsen hated pictures and vases on pianos, so he designed the diaphanous butterly-wing lid to be lightly concave. The guide told us it was tuned recently. The one-of-a-kind masterpiece is still played by a grandchild or great-grandchild.

Innovation’s downside

For all his poetic form-making, Aalto gave much creative attention to practical things like daylight and views, brick patterns, ventilation and plumbing. The guide pointed out tiny holes in the wood-slat ceiling of the living room, visible when you know to look. They’re about the size of a match-head and integrate with the ventilation system. There are 52,000 of these holes, as counted by the worker who recently had to clean them.

Aalto had the idea to open the living room entirely to the garden. He designed massive glass panels framed in wood that could slide away to nest behind the fireplace. The guide explained they’ve been opened only a few times in 85 years because it’s a whole production. The doors are heavy and fragile. Not to mention, in July, Finland’s perfect month, the mosquitos are killer. Maybe Aalto was ahead of his time.11

Aino and Alvar also designed the library walls to be moveable, so the living spaces could be reconfigured as the Gullichsens desired. Aino even designed hidden slot cabinets behind the bookcases for Mairea to store artwork, so she could rotate through her collection. But with zero acoustical privacy, Harry was driven nuts by the hubbub of four active kids running around the house. So they settled on a permanent location for the library walls and Aino designed an elegant closure of curved wood and glass panels to close the gap between them and the ceiling.

The kidney-shaped pool was the first of its kind, though certainly not the last. Soon, kidney-shaped pools were replicated throughout California, a comet-trail flaring from iconic to cliché in record time. Aalto’s was innovative, built without a foundation. It’s a concrete shell, floating like a boat on the subsoil. Eventually, it failed and was rebuilt in 2001. (Physics is a harsh mistress.)12

A graphic novel about Aalto’s life has a few panels depicting him diving into the pool to christen the house at the Gullichsens’ swank housewarming. But I can’t confirm it because when I google “did alvar aalto dive into villa mairea pool at housewarming” it returns only skateboarding links.13

Courtship

As a student, the more I read about this house, studied and diagrammed it, the more awed I was. I would notice a relationship between elements or a hidden geometry in response to an idea I’d read about, and just sit back stunned. Could Aino and Alvar really have this level of control over all aspects of their design? The very idea was thrilling. If naïve.

Design’s flow-state is similar to writing in the flow. After the initial ideas and sketches, the design or story begins to take shape and details rise spontaneously from a mysterious, subterranean river of creativity. These missives from the deep are rewards for patient attention, devotion and diligence. It’s not logical; it’s pure intuition. A dance of trust, an invitation, movement towards and away. A conversation between you and the muse: if I do this, what happens next? It can’t be forced, only courted.

Immersion

The house is now 85 years old, largely unchanged, still used by the family, and impeccably maintained. When we were there, a worker was up on the second-floor balcony making repairs. There he is, in his orange safety vest.

As much as I adore this house, writing about it has tested me. I want to do it justice—so you will love and admire it as I do. I want you to understand what a rare gem it is, a gem that is also a real family’s house that you can walk into and hear stories about. The guides ask you to take your shoes off in the entry, as if there can be any other response to walking into a rare work of art. Shoe shedding is a Finnish custom, but that’s beside the point. I would kneel down and bow if they asked me to.

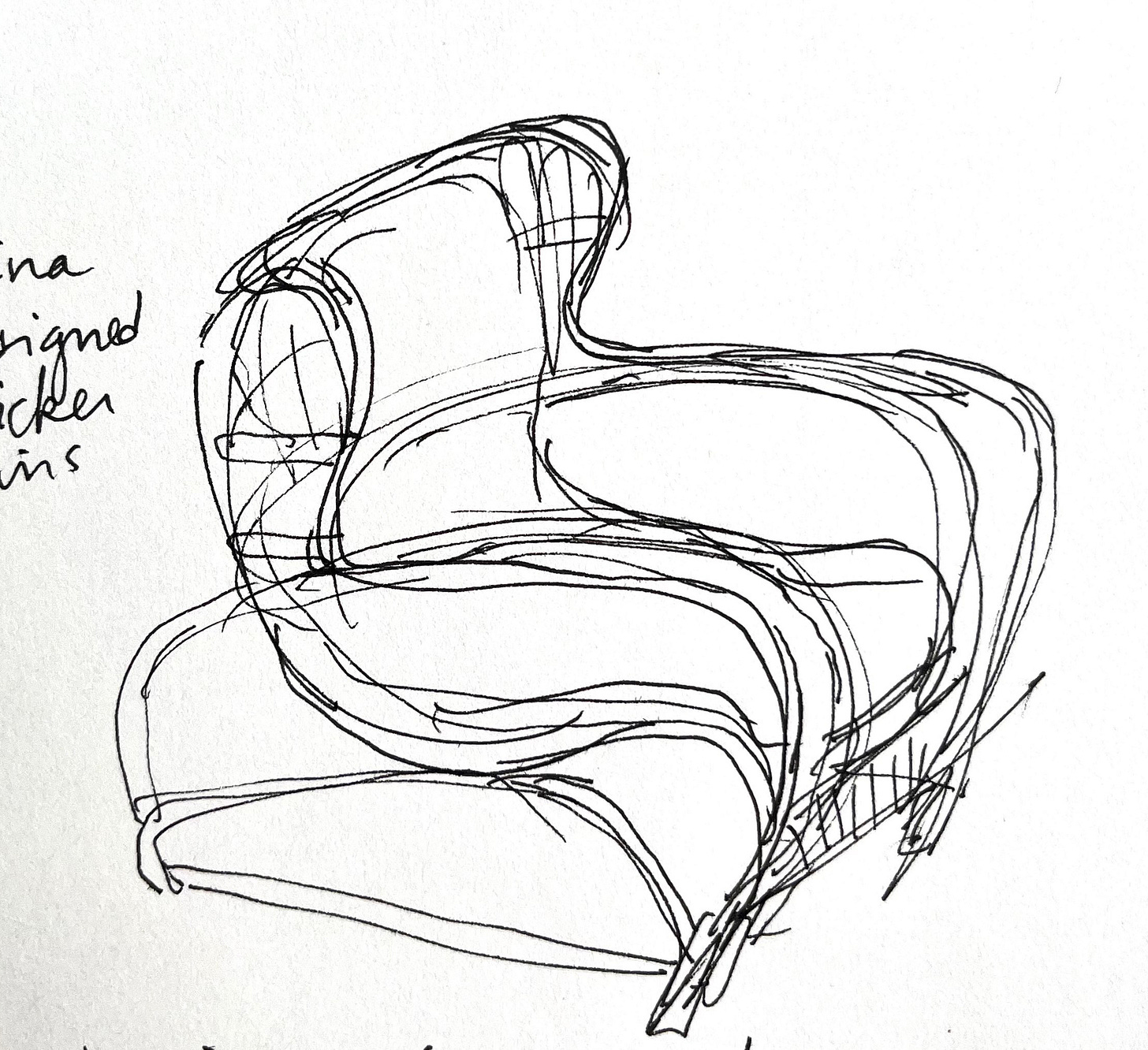

One of the most intractable rules was not to touch anything. Not anything. Not the wood handrail begging to be fondled. Not the juicy rattan binding columns together. Not the lickable leather lacing bronze door handles. Not the sensuous lover’s curves of the fireplace. Eyes only. Fingers itching, I longed for sudden-onset synæsthesia, to experience touch with sight. I almost managed it by sketching one of Aino’s custom-designed rattan and bamboo chairs. I felt those curves through my pen.

The narrative of regression from modern industrial to rustic primitive origins works. You can see it. You can feel it (though not with your fingers). This immersive place beguiles the imagination. At the sauna, I would soak in the intense heat, draw fire into my lungs, then dive off the rustic wood board into the jolt of frigid water, the shock, the whoop! of spastic in-breath. To be alive in this body in this rare place!

At the little gate,14 I would stand, awed. In my mind, I open it and walk into the forest to lose myself among the pines. I have all the time in the world. The sun doesn’t set until 11:00 pm.

Each season, we donate 30% of paid subscriptions to a worthy environmental cause. This post helped to raise $68 for Indigenous Environmental Network, Through a variety of alliances, they’ve been promoting environmental and economic justice issues for over twenty years. Track past and current recipients here.

What did you enjoy most about this essay? Have you been to any of Aalto’s buildings? I’d love to hear from you. Or share it with others by restacking on Notes, via the Substack app. Thanks!

My first foray here was a close read of Henri Labrouste’s masterpiece 19th century library, Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève in Paris. I’ve since written about tiny houses, architectural archetypes, the cellar as place and metaphor, the idea of home, and visiting a detail-rich private house in the Catoctin Mountains of Maryland.

In reality, this house was co-designed by Alvar and his equally talented wife and partner, Aino. For simplicity, I will continue with the singular pronoun “his” and the possessive “Aalto’s,” rather than the more contorted, “the Aaltos’,” except when I don’t. Aino Aalto likely didn’t receive full credit for her many critical contributions to their projects. I certainly never heard of her in school in the ‘80s.

Still am.

Typical either/or thinking of an architecture critic. Porphyrios, Demetri. Sources of Modern Eclecticism: Studies on Alvar Aalto. London: Academy Editions, 1982.

You may have noticed that architectural discourse uses simplistic dichotomies— building/site, heavy/light, open/closed, dark/light, solid/void, etc. These aren’t really absolutes. Whenever you see one of these pairs, imagine the yin-yang diagram, or a spectrum with opposites at each end and many shades of both in-between.

There are 8 bedrooms upstairs!

Any architect would kill for a commission like this. Architecture professors are fond of assigning such fantasy projects to students.

Artek is a portmanteau of art and technology.

Timeline of Aalto’s life from MOMA website. And History of Artek here. Read more of Maire’s fascinating, influential life here.

Maire continued to paint throughout her life, but never showed her work to anyone. The painting studio at her house is her private space, reached by hidden stair. Everyone knew never to go in there.

Thirty years later, in the 1970s, an Australian architect, Glenn Murcutt began designing hist houses with similar disappearing glass walls. On an earlier pilgrimage, we visited many of Murcutt’s houses and they are glorious. Their owners had nothing but glowing things to say about working with him, which amused me. They always served us fresh baked goods and offered coffee—they were convinced that Americans drink only coffee, not tea. Murcutt was awarded architecture’s Nobel Prize, the Pritzker, in 2002.

This is the very “pool that changed skateboarding,” the “origin of pool skateboarding— google “villa mairea pool” if you don’t believe me.

BTW, that three-volume graphic novel is worth a look if your library has it.

(the humble lattice of pine slats that I had read about and was careful to include in my diagrams as a critical player in the story)

Julie, through this bewitching and meticulous tribute to the house, I can imagine living my life there. Unlike Fallingwater, where I can't imagine living or even spending an evening, this work of art seems meant to nurture the occupants' best impulses, not to impose itself upon them. Thank you for the virtual tour.

Wow. Appreciated the guided tour to a magnificent home in the woods of Finland. I learned a lot about how to look at such a work of historical architecture. Brava.