Welcome to Talking Back to Walden. This is where we consider only the best passages of Thoreau’s 1854 classic, for what they might tell us about our present-day environmental woes and hopes. Last month, we spend a rainy afternoon with a magnificent triple poplar tree. This month, we consider ice as both companion and measure.

From Chapter 16: The Pond in Winter

“Ice is an interesting subject for contemplation.”

After a sublime opening image of the seemingly dormant pond, iced over and covered in a thick blanket of snow, Thoreau describes the canny ice-fisherman who come with their mysterious knowledge. Like this one catching massive pickerel with full-sized perch, “as if he kept summer locked up at home, or knew where she had retreated.” Thoreau is uncharacteristically generous with admiration for these men:

“His life itself passes deeper in Nature than the studies of the naturalist penetrate; himself a subject for the naturalist.”

He then describes his efforts, with the solid ice as a base, to discover the true depth of Walden Pond. Several pages later, he introduces the ice-cutters with an amusing extended passage imagining them scraping soil and ploughing to seed a crop:

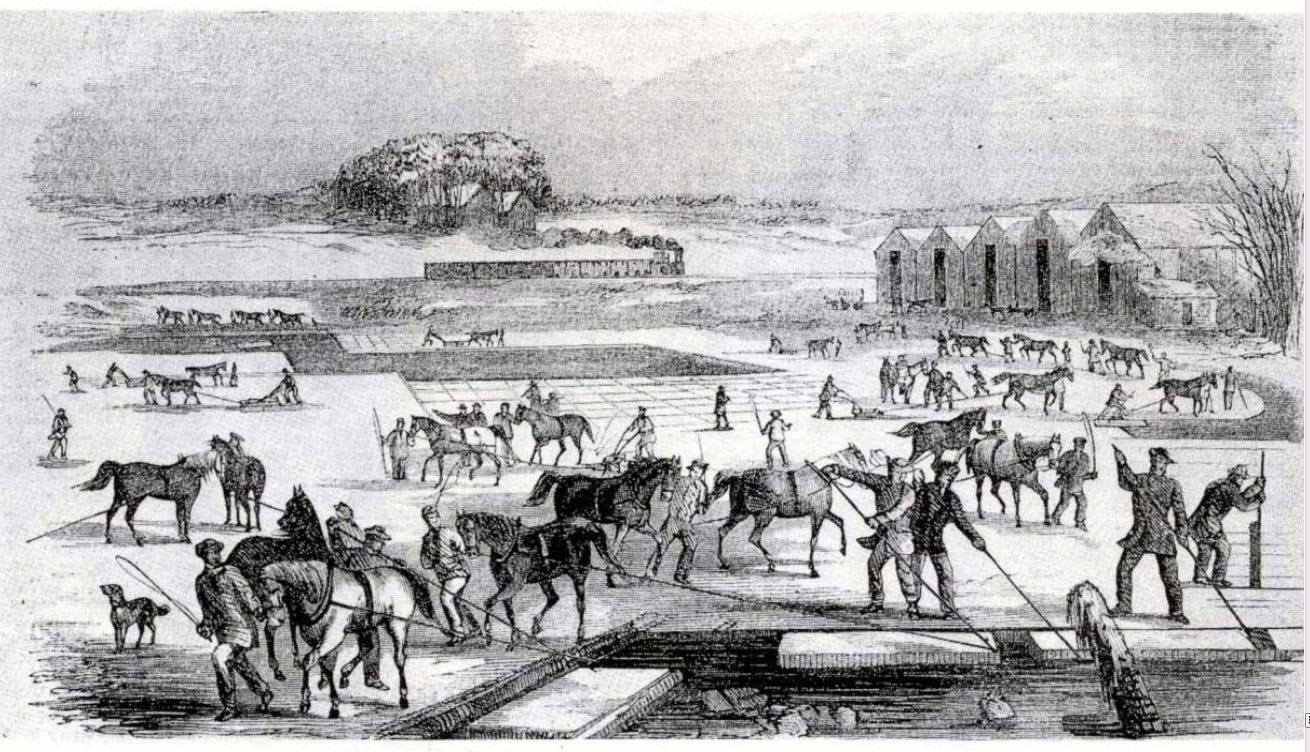

“In the winter of ’46-7 there came a hundred men of Hyperborean extraction swoop down on to our pond one morning, with many car-loads of ungainly-looking farming tools, sleds, ploughs, drill-barrows, turf knives, spades, saws, rakes, and each man was armed with a double pointed pike-staff, such as is not described in the New-England Farmer or the Cultivator.”1

The crop that year yielded 10,000 tons of ice. Thoreau’s contemplation of the magical appearance and properties of ice leads him to hint at the difference between, if not the value of, affect and intellect. In this single brief chapter, he gives cameos to the Mahabarata, Milton, Greek mythology, the Bible, and the Bhagavad Gita, leaving no doubt as to where he feels most aligned.

He wraps up with his fascinated appreciation of interconnectedness: the texts he studies on cold winter mornings originated in the very places to which the New England ice will be shipped:

“The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganges. With favoring winds it is wafted past the site of the fabulous islands of Atlantis and the Hesperides, makes the periplus of Hanno, and, floating by Ternate and Tidore and the mouth of the Persian Gulf, melts in the tropic gales of the Indian seas, and is landed in ports of which Alexander only heard the names.”

At the end of this passage, Thoreau compares vulnerable water to the toughness of ice, as “the difference between the affections and the intellect.” I think we know where his preference lies.

The transcript is at the end, if you prefer to read it.

Talking Back

The small silk bag is about four inches by three inches, tied-dyed indigo-cloud-lavender with tomato-red piping and trim at the draw-string closure. Inside are four Inuit cherts: two sand-color and two terracotta. Three are under an inch, the fourth a bit larger. They percuss brightly when shaken in my palm, slip into the bag with a muffled clack.

The bag was presented to my husband and me by a dear friend at a ceremony we held twenty-odd years ago for the child we lost. A newborn adoption placement that failed after he’d been with us for a week. A child for whom we had waited years, riding heart-wrenching ups and downs of surgery and loss. After this one my heart keened, What’s it going to take?

Presenting this gift to us, our friend told of Inuit waiting in the cold for the beluga to come in, for the seals to show, the caribou, the bears. While waiting, they used antler pressure-flakers to chip sharp tools of flint or chert. It was their waiting that she wanted us to feel as we held the bag in our hands, as we held the chips in our palms. Their waiting, their patience, their trust.

I’m standing on a cold January day beside a frozen pond. Here to investigate and experience the waiting state of frozenness. I carry the silk bag in my pocket. The cherts have led me here. I stand at the edge between a stubbly shoreline and an iced-over pond to admire the intricate lace of fallen leaves, moss, pebbles, and frozen water. I study the reflections of bare branches and sky in glisten-puddles of water atop ice. I listen to the wind in the trees and feel the warm sun on my face.

Come out here, says the ice. Leave the shore.

This sparks a sharp desire to be on the ice. Away from shore in a foreign land. But I’m cautious. I drop to hands and knees to shuffle forward a few inches.

More, says the ice. To the middle.

I lay myself out flat against the ice, the full length of my body, propped on forearms. A sphinx on the surface, low, looking around. The friendly cold soaks into me. Divine.

When it’s time to return, everything is fused, stuck tight. The resistant surface of ice pulls me close. I have to peel myself off.

If anyone knows ice, it’s the Inuit. If I listen well, with my heart open and my imagination tuned, those ancestors might tell me there is far more to ice than meets the eye. That I could learn to appreciate its gifts. The lessons of frozenness.

At that time, my son (the one who stayed) was in a state of frozenness, drawn inward, encased in a hard, cold shell, showing little outward signs of life. Yet there was much life in his dark depths, stirring beneath suspended animation. There was life, vulnerable life, trapped at the edges. Twigs, small pebbles, leaves caught mid-thought between land and water. When spring comes, it will all thaw. They will once again float free.

And spring will come. Spring always returns. The cherts of the Inuit ancestors remind me not to jump ahead, not to anticipate. But to return to the ice. Stay longer with the frozenness. Learn its otherness, be with not-knowing, resist judgment.

Embrace stillness. Quiet. Rest. Patience. Waiting.

Immersion

Bundle up. Venture outside and see what happens. You may wish to bring a talisman with you to guide your wander, something small and tactile.

Here are a few questions to carry with you:

How are you being called in your inner life to the same spareness you see around you?

What is winter’s secret, just for you this day?

What gift might I find by walking into the discomfort of winter?

At the same cold retreat where I encountered the frozen pond, my collaborator and mentor, Jim Hall, sent us out with these questions. He noted there is something about winter that invites us into an experience that is in many ways like a desert. A landscape foreboding and fierce, but one that in various religious traditions has been a place of profound spiritual transformation.

Jim cited Belden Lane’s book, The Solace of Fierce Landscapes, where he reflects on the experience of Desert Christians:

“My fear is that much of what we call spirituality today is overly sanitized and sterile, far removed from the anguish of pain, the anchoredness of place. Without the tough-minded discipline of desert-mountain experience, spirituality loses its bite, its capacity to speak prophetically to culture, its demand for justice.”

Witness

Founded in 2007 by James Balog, the Extreme Ice Survey (EIS) is an innovative, long-term photography program that integrates art and science to give a “visual voice” to the planet’s changing ecosystems.2

Jeff Orlowski’s stunning 2012 film, “Chasing Ice” follows Balog and his team of researchers to the coldest places on earth while they set equipment to collect evidence of climate change. The team’s obsession jumps off the screen, as they drive dogsleds across ice fields to ford glacial streams, climb rocks, and skirt bottomless crevasses to set and tend their equipment. They joke about the insanity of their endeavor.

“Putting really delicate electronics in the harshest conditions on the planet. It’s not the nicest environment for technology.”3

The heart-stoppingly gorgeous film teeters on emotional extremes. The team acknowledge the physical discomfort and dangers with wry understatement.

“Every once in a while, I’ll be thinking maybe that office job wasn’t so bad.”

They struggle for words in the face of what they’re seeing when they witness a colossal calving of ice the size of lower Manhattan. They reach for unironic metaphor.

"The calving of a massive glacier believed to have produced the ice that sank the Titanic is like watching a city break apart."

The team is aware of the legacy they’re creating with their witness. At the end of the movie trailer, Balog holds a camera memory disk between puffy gloved fingers.

“This is the memory of the landscape. That landscape is gone. It may never be seen again in the history of civilization. And it’s stored right here.”4

Measure

Thoreau’s descriptions of ice fisherman on Walden Pond put me in mind of a recent post from

about ice fishing in our time of climate change.5“On most January Sunday afternoons, I would ordinarily be poking holes in lake ice for the purpose of fish extraction, but in this iceless winter I’m poking around the internet for some historical lake ice data.” ~ Chris Jones, from “Ice Fishing, Climate Change and....”

I decided to see if there’s any chatter about the ice on Walden Pond. Of course there is.

A 2022 article profiles Andrew Robichaud, a Boston University history professor, who is writing a book on the industrial ice trade, which lasted from the 1820s to the 1920s. It’s a history of climate, ice, and the global ice trade that connected North America south to the Caribbean and South America, and east to Europe, as far as India, China and Australia.6

While modern refrigeration eclipsed the ice industry, climate change would render it impossible today. Ice-out and ice skating remain as the two comparative measures of pond ice then and now. BU biology professor Richard Primack wrote about ice-out, the date in spring by which the pond is 90% ice-free:

“Between 1995 and 2009, ice out ranged from February 22 to April 12, with an average of March 17--two weeks earlier than in Thoreau’s time. And in the record-breaking warm year of 2012, a thin ice surface only formed on January 19. Ice-out for the season was recorded only 10 days later on January 29, a startling six weeks earlier than ice-out in Thoreau’s time.”

He went on to note how the warmer water affects waterfowl, fish, and other creatures who make their homes in and around Walden Pond.7

Ice-skating is the other measure. NPR’s Science Friday shared an excerpt from Primack’s book, Walden Warming, about how ice-skating, a popular New England pastime in his childhood during the 1950s and 1960s, is now nearly non-existent.

“During the late 1980s and early 1990s, when I wanted to bring my own children ice-skating in such a natural setting, it was hard to find a suitable pond or lake in Newton. The winters were now too mild; without the long cold snaps of my boyhood, ice of sufficient thickness no longer formed.”8

Talking back to Walden together

In December, we shared our experiences of presence and sensory immersion outside. This month, let’s share what we discover in the chat as we explore winter’s spareness, experience the suspended state of frozenness, and listen for secrets.

Transcript of excerpt from Chapter 16: The Pond in Winter

. . . Every winter the liquid and trembling surface of the pond, which was so sensitive to every breath, and reflected every light and shadow, becomes solid to the depth of a foot or a foot and a half, so that it will support the heaviest teams, and perchance the snow covers it to an equal depth, and it is not to be distinguished from any level field. Like the marmots in the surrounding hills, it closes its eye-lids and becomes dormant for three months or more. Standing on the snow-covered plain, as if in a pasture amid the hills, I cut my way first through a foot of snow, and then a foot of ice, and open a window under my feet, where, kneeling to drink, I look down into the quiet parlor of the fishes, pervaded by a softened light as through a window of ground glass, with its bright sanded floor the same as in summer; there a perennial waveless serenity reigns as in the amber twilight sky, corresponding to the cool and even temperament of the inhabitants. Heaven is under our feet as well as over our heads.

. . . To speak literally, a hundred Irishmen, with Yankee overseers, came from Cambridge every day to get out the ice. They divided it into cakes by methods too well known to require description, and these, being sledded to the shore, were rapidly hauled off on to an ice platform, and raised by grappling irons and block and tackle, worked by horses, on to a stack, as surely as so many barrels of flour, and there placed evenly side by side, and row upon row, as if they formed the solid base of an obelisk designed to pierce the clouds. They told me that in a good day they could get out a thousand tons, which was the yield of about one acre. Deep ruts and “cradle holes” were worn in the ice, as on terra firma, by the passage of the sleds over the same track, and the horses invariably ate their oats out of cakes of ice hollowed out like buckets.

. . . At first it looked like a vast blue fort or Valhalla; but when they began to tuck the coarse meadow hay into the crevices, and this became covered with rime and icicles, it looked like a venerable moss-grown and hoary ruin, built of azure-tinted marble, the abode of Winter, that old man we see in the almanac,—his shanty, as if he had a design to estivate with us. They calculated that not twenty-five per cent. of this would reach its destination, and that two or three per cent. would be wasted in the cars.

. . . Like the water, the Walden ice, seen near at hand, has a green tint, but at a distance is beautifully blue, and you can easily tell it from the white ice of the river, or the merely greenish ice of some ponds, a quarter of a mile off.

. . . Perhaps the blue color of water and ice is due to the light and air they contain, and the most transparent is the bluest. Ice is an interesting subject for contemplation. They told me that they had some in the ice-houses at Fresh Pond five years old which was as good as ever. Why is it that a bucket of water soon becomes putrid, but frozen remains sweet forever? It is commonly said that this is the difference between the affections and the intellect.

Thanks for reading Talking Back to Walden. Read previous months here: September, October, November, December. If you enjoyed this, please share. For more like it and for my regular weekly posts, please consider becoming a free or upgrading to paid subscriber.

Another way to show love is to share this post with others by restacking it on Notes, via the Substack app. Thanks!

In Greek mythology, the Hyperboreans (Ancient Greek: ὑπερβόρε(ι)οι; Latin: Hyperborei) were a mythical people who lived in the far northern part of the known world, from Wikipedia.

Extreme Ice Survey website. The homepage features video time-lapses of deflating, receding glaciers.

Balog’s other website is Vanishing Ice.

Find the article, “Tracing the History of New England’s Ice Trade: BU history professor studies long-gone industry, and how climate change would have made it virtually impossible today,” here. Published Feburary 4, 2022 in BU’s online magazine. This video includes fascinating 1920s film footage of the ice-cutting tools and technologies that were used for 100 years.

From his blog, Climate change in partnership with Thoreau, this post on March 24, 2013. I wrote about Primack’s research on the effects on the ecosystem of early leaf-out in October’s Talking Back to Walden. A summary of his 2014 book, Walden Warming, is here.

Find the excerpt on the Science Friday website

And I like the watercolour!

Winter has a beautiful stillness that doesn't exist in other seasons and you captured it with great insight and detail. It's sad that the seasons are starting to blend together slowly.