Welcome to Talking Back to Walden. This is where we consider only the best passages of Thoreau’s 1854 classic, for what they might tell us about our present-day environmental woes and hopes. This month takes on a dauntingly vast subject: shelter. I limbered up with this consideration of tiny houses, which seem to have universal appeal including here on Substack. The original tiny house was built by Thoreau himself:

Thoreau raised many thoughtful points about shelter, ranging from economics to aesthetics to metaphysics.

appreciates this in a recent post: “I think that Thoreau's enduring value lies not in the answers he found, but in the questions he asked.”1Our son’s 3rd grade class studied the shelters and lifeways of cultures around the world. He chose the Hausa people because, as he wrote in his report, “I would like to live in a tree.”2 Each child built a detailed model of their house in its environment, including people and animals and food modeled from beeswax. One of the most appealing things about their creations is the use of natural materials in clever ways. If only our housing could be in such intimate relationship with the natural world today. Like a bird’s nest.

I’ve been saving this gem from to set the mood for today’s consideration of home, and shelter:

“[H]ome is where we put the heavy things down. And home is where we are forgiven.”3

A housekeeping note: I’m incubating a monthly journal to feature great nature writing here on Substack, including guest posts, interviews, and creative community-building. The tentative name is Nature Writers Circle. I will donate 35% of paid subscriptions to our favorite nature and/or climate charities. Recommend your favorite and subscribe for launch updates.

From Chapter 1: Economy

“This frame, so slightly clad, was a sort of crystallization around me, and reacted on the builder.”

In a previous Talking Back, we read Thoreau’s scathing critique of the true cost of houses to renters and owners alike. In this same chapter, when he describes the building of his cabin, he uses more direct, sensory language. You can almost smell the sawdust and pine pitch and sweat of his labor.

The story of his transaction with the Irish family from whom he bought a shanty includes observations of their squalor. While Thoreau carts boards to his new building site, their neighbor transfers all “the still tolerable, straight, and drivable nails, staples, and spikes to his pocket,” then justifies his theft as “a dearth of work.” Thoreau’s telling has less judgment than bemusement.

He gleaned timber, stones and sand “by squatter’s right,” and priced out his purchased materials, for a total cost of $28.12½.4

The building of one’s own dwelling lodges in the imagination as empowerment and self-sufficiency. Thoreau challenges the modern insistence on specialization:

“It is not the tailor alone who is the ninth part of a man; it is as much the preacher, and the merchant, and the farmer. Where is this division of labor to end? and what object does it finally serve?”

He characterizes architects as obsessed with ornament, which he sets in opposition to truth. He’s not the first and wasn’t the last to call out shallowness—in architecture or in literature. Or in his fellow man.

“What of architectural beauty I now see, I know has gradually grown from within outward, out of the necessities and character of the indweller, who is the only builder. . .”

(In case you’re wondering, the barking dog at 0:50 is indeed Brody, the same doofus who sings for paid subscribers.) The transcript is at the end, if you prefer to read it.

Talking back

Shelter is a need so essential that Maslow built his entire pyramid on its foundation, accompanied by air, water, food, sleep, clothing, and reproduction. To have a roof over your head, and a place to lay that head to sleep. To be housed. Being unhoused is—or should be—unthinkable. (More on that below.)

I’ve lost track of the number of houses I’ve lived in, designed, remodeled, workshopped, helped to build. Shelter is something I’ve always taken for granted. Oddly, though I do have a professional relationship to the house as both idea and fact, I feel no more qualified to write about it than any other human.

The house shelters our bodies and our imaginations, along with our ancestral history and memories. As my first architecture professor asked, What does it mean to make a mark upon the land? The house, as an intentional human artifact both physical and metaphysical, dwells deep within our personal and cultural subconscious as dreams and metaphors.5

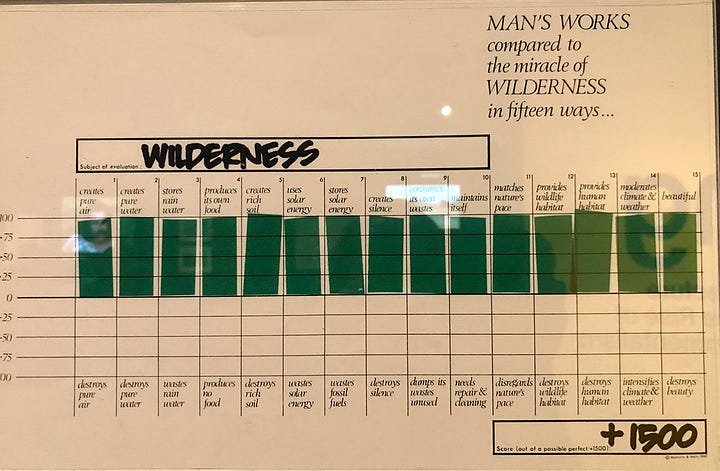

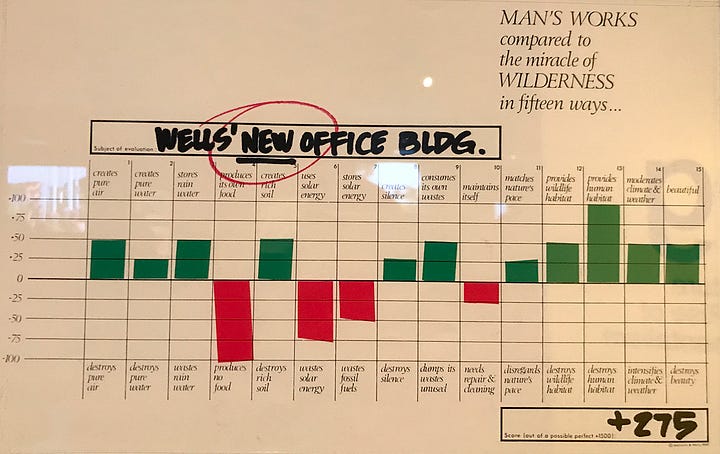

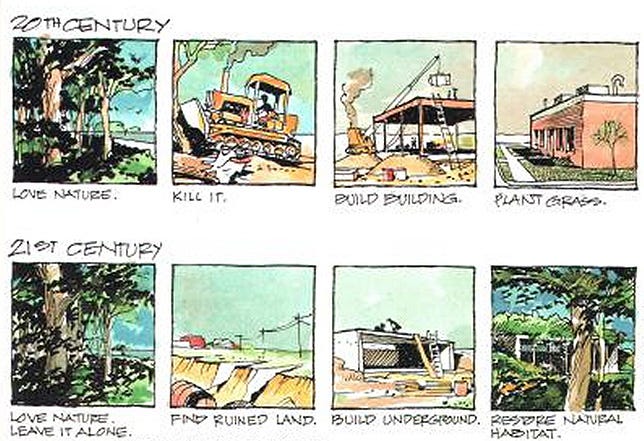

This question of meaning drifts into one of measure. What makes a house “good”? One of my mentors, Malcolm Wells, advanced a modest proposal for this. The grandfather of underground architecture, his mind was brilliant, his imagination rich, his humor clever, and his drawing hand lyrical. He proposed that we measure human artifacts in comparison to nature’s design genius. He asked, If nature, specifically wilderness, is our design standard, how do our buildings and cities measure up?

Later, the architect William McDonough put it this way: How can a building be like a tree? How can a city be like a forest? These questions are poetic echoes of Thoreau’s whole enterprise. There is more to probe here, including the feeling of being in a forest, that sense of belonging and otherness captured so well by David Wagoner in his poem, “Lost”:

Stand still. The trees ahead and bushes beside you Are not lost. Wherever you are is called Here, And you must treat it as a powerful stranger, Must ask permission to know it and be known. The forest breathes. Listen. It answers, I have made this place around you, If you leave it you may come back again, saying Here. No two trees are the same to Raven. No two branches are the same to Wren. If what a tree or a bush does is lost on you, You are surely lost. Stand still. The forest knows Where you are. You must let it find you.

Whether the Hausa did or not, our proto-human ancestors lived in trees for millennia. A newborn infant has surprising grip strength—enough to hold her own body weight. I imagine this as a remnant of needing to cling to Mother, to defy gravity and remain in her safe embrace.

Modern houses today go far beyond basic shelter. They also provide comfort—and here is where we run into trouble.

“I’m reminded anew of the tax our entitled comfort relentlessly forces on the world.”6

Comfort is a serious business in my profession. To question entitlement to comfort would be to court malpractice. But such entitlement inherently means separation, even estrangement, from the wider world of our wild kin— what we in our thoughtless distancing call nature or the environment.

A house is clothing, writ large. Yet it’s far simpler and more efficient to heat a body than a whole house. Clothing is one of our best inventions. We can put on an extra layer or two to keep warm. We can dress lightly in hot weather. Why not design a house with layers that function like clothing, to be removed or added to suit the weather and time of day?

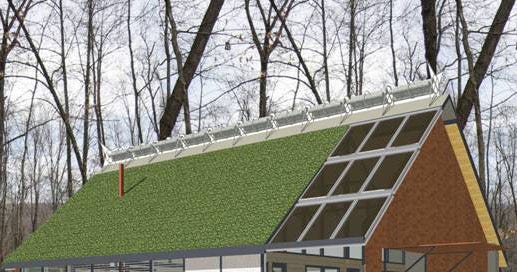

To build a house with care and intention is one way to repair our estrangement with the natural world. In A Good House, the environmental journalist Richard Manning chronicles the year he did just that:

“The building of a house seemed a simple, straightforward act of love, and slowly it was occurring to me that such acts are what we need right now.” (p.6)

He set out to challenge the notion that

“We inhabit houses, but neither we nor our houses inhabit their places.” (p.4)

Walking in a forest near Missoula that had somehow escaped logging, he notes that in the dark canopy, we

“have surrendered control. Control is a house or tents or motors, and here there are none of these things. Control is a resistance to natural forces. Control is a fear of death.” (p.204)

The professional mindset of entitlement to comfort relies on control. Architects and engineers employ techniques and materials to keep moisture out, hold heat in, dehumidify, or cool—these are expected, essential.

Yet, control of nature is what caused all the trouble we’re in now, this burning earth and degraded ecosystems. Who says ruthless control is the only way to achieve comfort? Thoreau’s Walden is an extended reminder of the many virtues and joys of partnership and sufficiency. Open a window, put on a sweater, better yet, go into our one true home—outside.

Immersion

This month, let’s try a short writing exercise. At the end of this introduction, I’ll include a few prompts and questions that you can either read or listen to. Sit in a comfortable place, either inside or outside. Close your eyes. Briefly scan your body, from feet to head, pausing at any places where you notice that you’re holding tension. Breathe slowly, in and out a few times, further releasing any tension. You might try breathing in through your nose to a count of four, and out your mouth with a sigh, to a count of five. But no need to force it. Once you feel present and relaxed, consider these questions. Give yourself a few minutes to let the thoughts come, then open your eyes, and write down anything you saw, heard, or remembered. No judgement, just write until you get it all down.

Where have you felt most at home? Describe that place. What does the place feel like? What sounds are present? What can you smell? Are you alone or with others? Where is home, for you?

Wisdom

Thoreau can come off as a cerebral, erudite name-dropper. Thankfully, Walden also includes striking passages of observation and appreciation of nature. Where Thoreau supplemented his personal notes with citations gleaned from an extensive education in the western canon, contemporary nature writers show another way to explore our connection, through direct sensory engagement.

One of my favorites is Lauren Groff, whose recent book, The Vaster Wilds, follows an indentured servant girl of about fourteen on her harrowing escape from the famine and violence of an early unnamed colonial outpost. The girl is driven to survive, equipped with practical knowledge and surprising resourcefulness. Her courage and persistence manifest as a lack of resistance sourced from a deep, intuitive connection to nature. Not as a benign force—the harsh elements threaten her vulnerable animal body—but as a partner offering shelter necessary to her survival.

After her long flight through the winter night, she finds a crevice within boulders near the river, “barely larger than her own body.” She presses herself into the cleft away from the wind to warm up and thaw her fingers enough to extract from her sack the items she’d stolen before her escape: woolen shawls, a hatchet, a knife, a flint, and a cup. She manages to gather wood to build a fire in the rocks and spreads a shawl over the top to make a flat tent.

“The comfort of her hovel now was so mightily unexpected that it soothed the sharpness of her panic and horror, and she fell into a quick deep sleep. She slept so full that if a beast had neared and licked her face, or if the sharp and slinking soldier who was even now following her tracks through the dawn had leapt these many miles in a blink and silently stolen upon her with a knife in his hand, she could not have waked enough to find herself afraid.” (p.33, eBook)

Further along her journey, she shelters in a giant hollow log, which comes with its own food source: nutritious grubs that restore her flagging strength. Shelter at its most elemental.

Measure

In its spring 2024 sitting, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments in the case, City of Grants Pass v. Johnson, a case brought against the town in Oregon that outlawed camping in public places, essentially making homelessness illegal.7 On the New York Times “Daily” podcast, the host opened with the shocking statistic that the number of homeless people has surged in the U.S. to “more than 653,000, a 12% population increase since last year.”8

For her master’s degree thesis, University of Maryland alumna Leah Clark explored how architecture might be used to alleviate the pervasive, interlinked problems of building lot vacancy and homelessness in West Baltimore. As she says,

“Housing is a human right. A place to call home is not only connected with safety and self-worth, but with our very humanity.”9

Houselessness is dehumanizing, one of the points made in a recent multimedia feature by the New York Times.10 The journalist who shaped this story, Lori Yearwood, was homeless herself for two years. She spoke at the 2022 Supportive Housing Conference, saying, “My story is society’s story.” Her purpose was to shift and widen our perspective of the unhoused, to spur radical change. She called out ways that we blame and shame the unhoused, many of whom are trauma survivors.11

“Society’s projections about the unhoused, coupled with systematic structural racism are magnified in homelessness, a place where people are routinely stripped of their self-agency.”

Black Americans comprise 13% of the general population, but 40% of the homeless population. Since we associate being housed with belonging, seeing the unhoused reminds us that something is broken. We view the unhoused as “a bundle of pathologies,” in Lori Yearwood’s words, a “problem that needs to be fixed.” In reality, many folks are often repeatedly traumatized while unhoused.

Homelessness is a multi-faceted systemic problem that requires a diversity of people to work together to address, and ideally solve. With rare exceptions, few journalists attempt to convey this systemic nature. A story is either about the high cost of housing or being one paycheck away from bankruptcy or a Supreme Court case or trauma or systemic racism or addiction or mental health or or or. It’s no wonder reporters resist following multiple threads into the impossibly tangled, confusing snarl. Who wants to read that?

I was particularly struck by the “Daily” podcast reporter’s closing remark about the significance of the recent court cases on homelessness:

“And if these cases fall, it remains to be seen whether cities do try to find all these creative solutions with housing and services to try to help people who are homeless or whether they once again fall back on just sending people to jail.”

In my head, a voice screamed, Are you f***ing kidding me? HOW MUCH DOES JAIL COST?? So, I looked it up.

“Based on FY 2022 data, the average annual COIF for a Federal inmate housed in a Bureau or non-Bureau facility in FY 2022 was $42,672 ($116.91 per day). The average annual COIF for a Federal inmate housed in a Residential Reentry Center for FY 2022 was $39,197 ($107.39 per day).”12

And to house that person instead of jailing them?

“A homeless person costs approximately $30,000-$50,000 per year in supportive services. Two years of that is enough to pay for an entire house in some cities. There are about 500,000 homeless individuals in the U.S. The price tag to treat the malady of homelessness works out at least $15 billion per year. How does it make any sense not to just fix it?”13

And here is where measure always seems to end up. Putting price tags on human beings. Costing out our neighbors. Foisting those costs—that don’t even begin to solve the problem—onto long-suffering taxpayers. There has to be a better way.

Talking back to Walden together

If you are moved to share your writing about where you’ve felt most at home (see Immersion section above), here’s a chat thread for you.

Transcript of excerpt from Chapter 1: Economy

Near the end of March, 1845, I borrowed an axe and went down to the woods by Walden Pond, nearest to where I intended to build my house, and began to cut down some tall, arrowy white pines, still in their youth, for timber.

. . . I hewed the main timbers six inches square, most of the studs on two sides only, and the rafters and floor timbers on one side, leaving the rest of the bark on, so that they were just as straight and much stronger than sawed ones. Each stick was carefully mortised or tenoned by its stump, for I had borrowed other tools by this time. My days in the woods were not very long ones; yet I usually carried my dinner of bread and butter, and read the newspaper in which it was wrapped, at noon, sitting amid the green pine boughs which I had cut off, and to my bread was imparted some of their fragrance, for my hands were covered with a thick coat of pitch. Before I had done I was more the friend than the foe of the pine tree, though I had cut down some of them, having become better acquainted with it.

. . . By the middle of April, for I made no haste in my work, but rather made the most of it, my house was framed and ready for the raising. I had already bought the shanty of James Collins, an Irishman who worked on the Fitchburg Railroad, for boards. James Collins’ shanty was considered an uncommonly fine one . . . The bargain was soon concluded, for James had in the meanwhile returned. I to pay four dollars and twenty-five cents tonight, he to vacate at five tomorrow morning, selling to nobody else meanwhile: I to take possession at six.

. . . I took down this dwelling the same morning, drawing the nails, and removed it to the pond-side by small cartloads, spreading the boards on the grass there to bleach and warp back again in the sun. One early thrush gave me a note or two as I drove along the woodland path.

. . . At length, in the beginning of May, with the help of some of my acquaintances, rather to improve so good an occasion for neighborliness than from any necessity, I set up the frame of my house. No man was ever more honored in the character of his raisers than I. They are destined, I trust, to assist at the raising of loftier structures one day. I began to occupy my house on the 4th of July, as soon as it was boarded and roofed, for the boards were carefully feather-edged and lapped, so that it was perfectly impervious to rain, but before boarding I laid the foundation of a chimney at one end, bringing two cartloads of stones up the hill from the pond in my arms. I built the chimney after my hoeing in the fall, before a fire became necessary for warmth, doing my cooking in the meanwhile out of doors on the ground, early in the morning: which mode I still think is in some respects more convenient and agreeable than the usual one.

. . . It would be worth the while to build still more deliberately than I did, considering, for instance, what foundation a door, a window, a cellar, a garret, have in the nature of man, and perchance never raising any superstructure until we found a better reason for it than our temporal necessities even. There is some of the same fitness in a man’s building his own house that there is in a bird’s building its own nest. Who knows but if men constructed their dwellings with their own hands, and provided food for themselves and families simply and honestly enough, the poetic faculty would be universally developed, as birds universally sing when they are so engaged? But alas! we do like cowbirds and cuckoos, which lay their eggs in nests which other birds have built, and cheer no traveller with their chattering and unmusical notes. Shall we forever resign the pleasure of construction to the carpenter? What does architecture amount to in the experience of the mass of men? I never in all my walks came across a man engaged in so simple and natural an occupation as building his house. We belong to the community.

Thanks for reading Talking Back to Walden. You can find a Table of Contents to the series here:

If you enjoyed this post, a lovely little 💚 keeps me going. For more like it and for my regular weekly posts, please consider becoming a free or upgrading to paid subscriber.

Another way to show love is to share this post with others by restacking it on Notes, via the Substack app. Thanks!

I couldn’t find evidence that the Hausa actually lived inside trees. There are mythic stories of ancestors and spirits residing in trees, which accounts for their abiding reverence for them.

In the post, every Death and every Bird

Scholars have noted that Thoreau was living on Emerson’s land by arrangement, so hardly a squatter. Details.

“Supreme Court hears case on whether cities can criminalize homelessness, disband camps,” PBS article here. As of this writing, no ruling has been issued. You can track it on SCOTUSblog here. A summary of the case and question at the heart is here.

You can listen to an interview with Leah on the Building Hope podcast.

Video interviews with unhoused people (gift link).

From the Federal Register

Ending homelessness would cost far less than treating it. For the cost, this article is cited: “Beyond Human Cost, D.C. Homelessness Comes With a Big Price Tag”

"Where have you felt most at home? Describe that place. What does the place feel like? What sounds are present? What can you smell? Are you alone or with others? Where is home, for you?"

An irresistible set of questions, especially for someone who grew up with powerful roots in a place, but equally powerful alienation from the conservative religious atmosphere of my home and family sphere. So it's not my parents' house where I feel most at home. But it is, without doubt, the Pacific Northwest, and particularly those corners in northwestern Montana and northern Idaho that I came to know intimately as a young man working with the Forest Service. The Yaak Valley. The Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness. The Moose Creek Ranger Station above the Selway River, for which my son is named.

I'm writing about one of those places on Tuesday -- but even outdoor spaces can be hard to go home to later in life.

I think part of this is that as "at home" as I have felt in these places, I have never shared them with anyone who could see them as I did. Except for my friend Connie Saylor Johnson, who disappeared into the Selway some years ago now for reasons no one knows. But I think she felt she was going home.

https://www.selwaybitterroot.org/csj

Clothing writ large! That instantly made me relate to my house differently. I was thinking just the other day that I feel most the sense ‘I’m home’ when I walk into our garden, more so than when I walk into our house, but I’m feeling into the idea of them really being one and the same.

My mind is rattled by the figures around homelessness. Over the years, during conversations about homelessness both participated in and overheard, I’ve lost a lot of faith in humanity.

Btw, I would also like to live in a tree.