“Shelter is one of the most important things to us, it divides us into the ‘normal’ and the homeless, it protects from weather, from the wild, from each other, it is home.” ~ Alexander M. Crow

I keep running across posts about shelter or houses. In “Delve,” considers caves as our first dwelling places. At the other end of time, writes in “Face Value” about fighting with Richard over exterior renovations to her house. She gets it. Houses can be sneaky:

“These are things Richard cares about more than I do. Such as what makes a house work so it won’t kill you.”

Maybe I’m seeing these essays because I’ve been working on this month’s Talking Back to Walden about—you guessed it—Shelter. It’s finally time to watch Thoreau build his famous cabin. Come Sunday, I’ll tackle the meaning of shelter and the scourge of homelessness. Being a big fan of coincidence and synchronicity, I was shaken (and amused) by

’s recent post, “You’re Not As Random As You Think.” The world is even weirder than I thought, and I’m here for it.May’s Talking Back to Walden comes out Sunday. Subscribe and it’ll land in your inbox, no coincidence required.

I wrote today’s post originally in response to

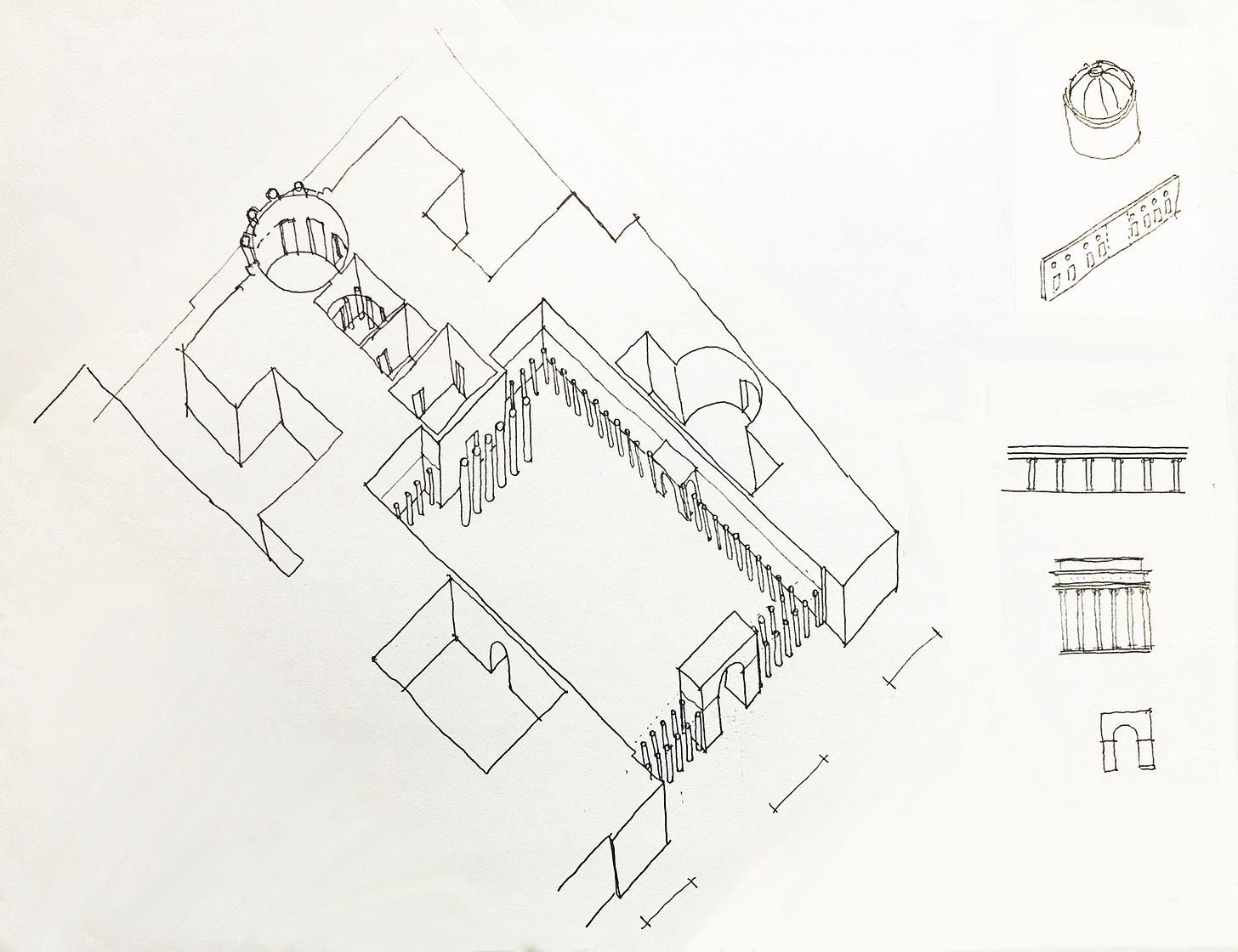

’s question about metaphor in architecture.1 This endlessly fascinating topic takes us far beyond the necessity of shelter into the realm of art. Whole books have been written and stuffed into our library for students to discover (or, more recently, ignore). Today is a peek into the world of meaning and symbol, which in architecture are less about specific styles and more to do with archetypal forms. Like a dome represents the world, for example.

I explored these ideas in my graduate architecture thesis on The Detail in Architecture. I still remember sitting outside on a bench in the May sunshine with my advisor. She hinted that it could become a book. At the time, I thought, Ha. There are enough books in the world as it is. Nobody needs this one. (Self-esteem wasn’t my strong suit.)

I continue to refer to that research when I teach Integrated Design Studio, an advanced graduate course that runs in the fall. Our team of faculty and professional consultants approximates the phase in a real office called Design Development when the team makes decisions about the structural system, materials, heating, cooling and lighting, and the myriad construction details necessary to bid on and build a project.2

Our whole message in this studio is that you can’t possibly make all those decisions without a clear, overarching vision of the building. We use the shorthand term, Big Idea, as in, “What’s your Big Idea and can you diagram it?” By that, we mean, what is your building about? What does it mean? And what form do those ideas take?

These are tough questions for any architect and particularly for grad students with limited experience. One way we convey such an abstract notion is through the study and analysis of great buildings—which was the approach I used in the post about the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève. (It’s linked in footnote 1 below.)

My thesis reviewed foundational architectural theory from the ancient Roman Vitrivius to the 18th- and 19th-century French crew of Laugier, Blondel, Durand, Quatremere de Quincy, Viollet-le-Duc, Guadet and Choisy, to the German Gottfried Semper, including contemporary theorists.3 I wanted to examine the central question of architecture: What makes a building more than mere shelter?

My thesis concluded that all great buildings are designed with a dynamic interplay between idea, form, and materiality. Forms symbolize ideas and meanings particular to a culture. Some forms are so archetypal as to seem universal. To return to domes, the circle as an idea is sacred to all human cultures, whether it stands for the world, wholeness, or the embrace of the eternal. It also happens to be a very stable form: arches and domes transfer vertical loads in a uniquely spatial way that a simple straight beam cannot. An arch or a dome can be built with different materials—stone, concrete, brick, steel, even wood.

To make it even more interesting, materials themselves have connotations that add another layer of symbolism. Stone might convey permanence or high status, brick is comparatively humble and wood, being organic, might seem downright temporary. The dome of the Pantheon in Rome was built of concrete and stone. It still floats up there after nearly 1900 years. (Isn’t that mind-blowing?) Standing in that space, it’s not a stretch to feel it as a representation of the world, even the cosmos. And the shaft of light pouring through the oculus at the top is a radiant axis-mundi to mark Rome as the center of the world.4

Theorists from Vitruvius to Laugier used “the first house” to illustrate the symbolic content of shelter.5 Gottfried Semper’s first house gives his story of how architecture progressed from mere problem-solving to metaphor. It’s also an argument for the continued relevance of this potent idea even today, as rapid innovation pushes us to leave the past behind. Human beings are always and ever in relationship with the world around us: with the phenomena of heat and cold, sunlight and moonlight, rain and wind, and with other beings both human and non-human. These relationships go far beyond the functional to the ontological.

Similar to archetypal characters and plots in literature, architecture also uses archetypes—forms so elemental, they appear in multiple cultures and centuries. A roof might be a circle (dome) or a triangle (pitched). Children’s drawings of houses the world over have delightful similarities, including the iconic peaked roof. Sure, that pitch is a practical way to drain rain off. But when a peaked form goes beyond signifying shelter to mean “home,” that shifts from function to symbolism. In The Poetics of Space, Gaston Bachelard speculated about what our dream images mean as we wander cellars and attics, and drift up or down stairs. It’s full of gems like, '“One always goes down the cellar stairs,” and “Up near the roof, all our thoughts are clear.”

In the Greek temple, the peaked roof was used intentionally to symbolize the “sacred mountain,” a vertical form connecting heaven and earth. It calls down into our midst the heavenly being to whom the temple is dedicated, Hera in this case:

People recruited archetypal forms to enshrine their deities and to reveal the sacredness of a place. Expressing the eternal is taken literally at this venerated Shinto shrine in southeastern Japan, which is rebuilt piece by piece every twenty years on an adjacent site. The buildings there now date from 2013 and are the 62nd iteration. The next ritual rebuilding will be in 2033.

Some architects layer on additional meanings to leave their mark on these forms. In the 20th century, Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier used the roof to demonstrate their own theories of architecture.

From early in his career, Wright played with the roof as a carrier of meaning, as in the Winslow House above. The roof extends beyond the walls and the upper band of windows is painted a dark color to exaggerate the overhanging symbolism of shelter. Wright was so taken by the Midwest’s wide open, horizontal landscape that he flattened his roofs to imitate the vastness of the prairie.

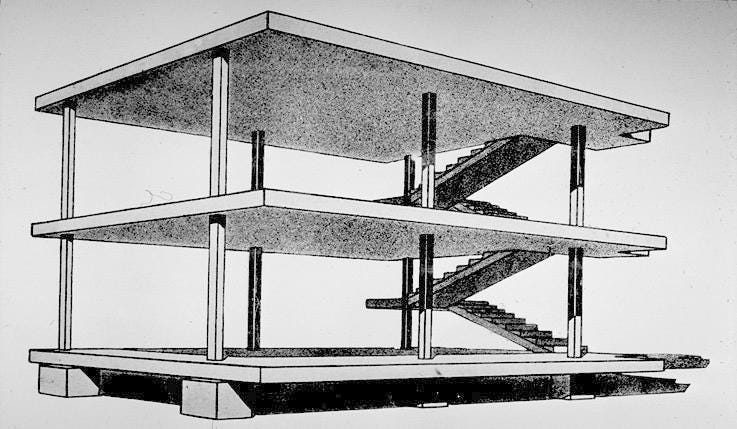

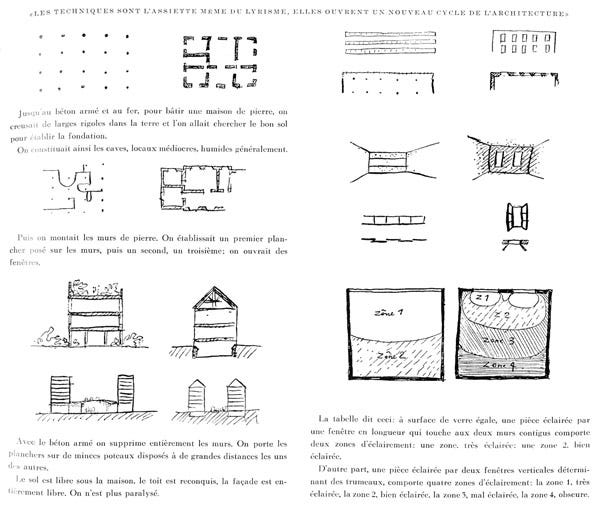

True to his French heritage, Le Corbusier was full of theories about architectural form. He took his inspiration not from place or culture, but from materials engineering. The poetry of his form departed from ancient, embedded meanings. Early in his career, he wrote a manifesto called Vers Une Architecture, complete with diagrams of an ideal architecture that embraces modern technology for a new age.

Le Corbusier’s Five Points of a New Architecture illustrated above were: Pilotis (columns instead of bearing walls), roof garden, open floor plan (figural spaces enclosed by non-loadbearing walls), long windows and open facades (because exterior walls need no longer carry roof loads). In the third set of diagrams on the left, you can see his argument against pitched roofs, which he saw as archaic and unnecessary. As a Parisian, he obsessed over giving everyone access to light and air, so why not use the tops of apartment buildings? His roof terraces reclaimed wasted space for recreation.

Going back to my response to Priya from the beginning of this post—that meaning and symbol are less about specific styles and more to do with archetypal forms—you can see that Le Corbusier and other modernists did much to challenge that. By tossing symbolism as archaic, modern architects participated in the overall project of modernity to liberate humanity from the past and its heavy burden of dead, useless prototypes. Sadly, this has resulted in a whole lot of soulless, ugly buildings looming over our daily lives.6

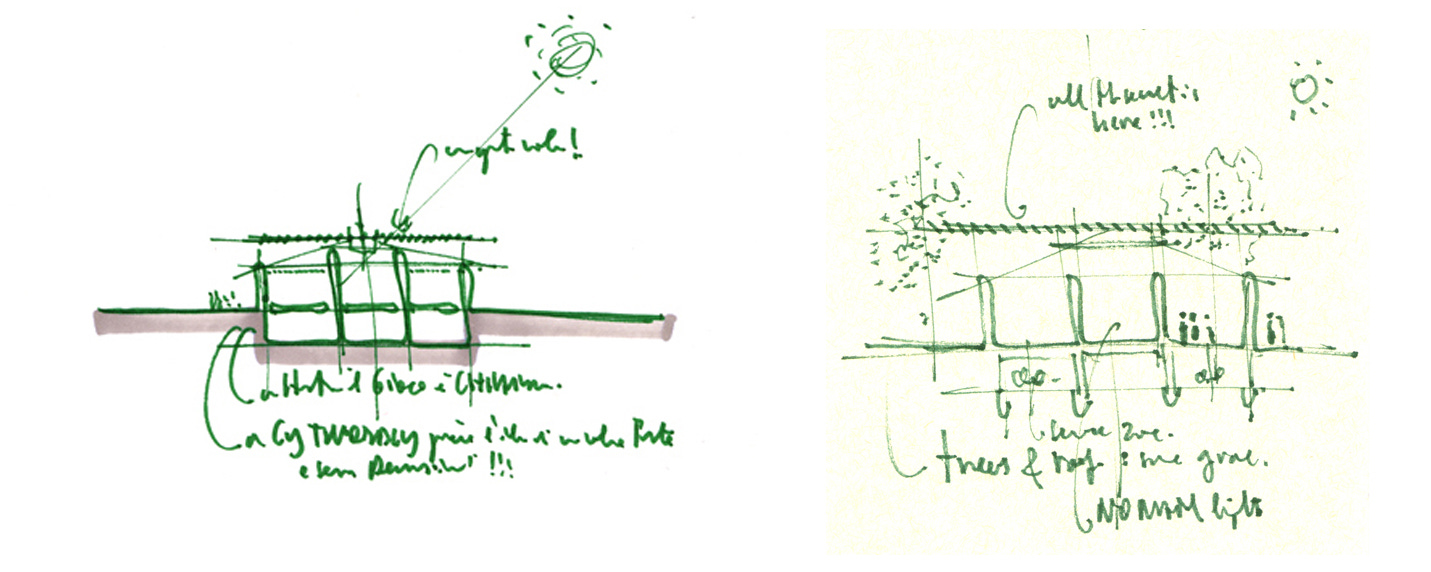

So where does all this leave us today? You may be relieved that contemporary architects don’t buy the notion that architecture is purely functional, that form doesn’t carry meaning. A building like Renzo Piano’s Cy Twombly Pavilion can be read as a direct response to Semper’s four elements (illustrated above), especially the enclosure and the roof.

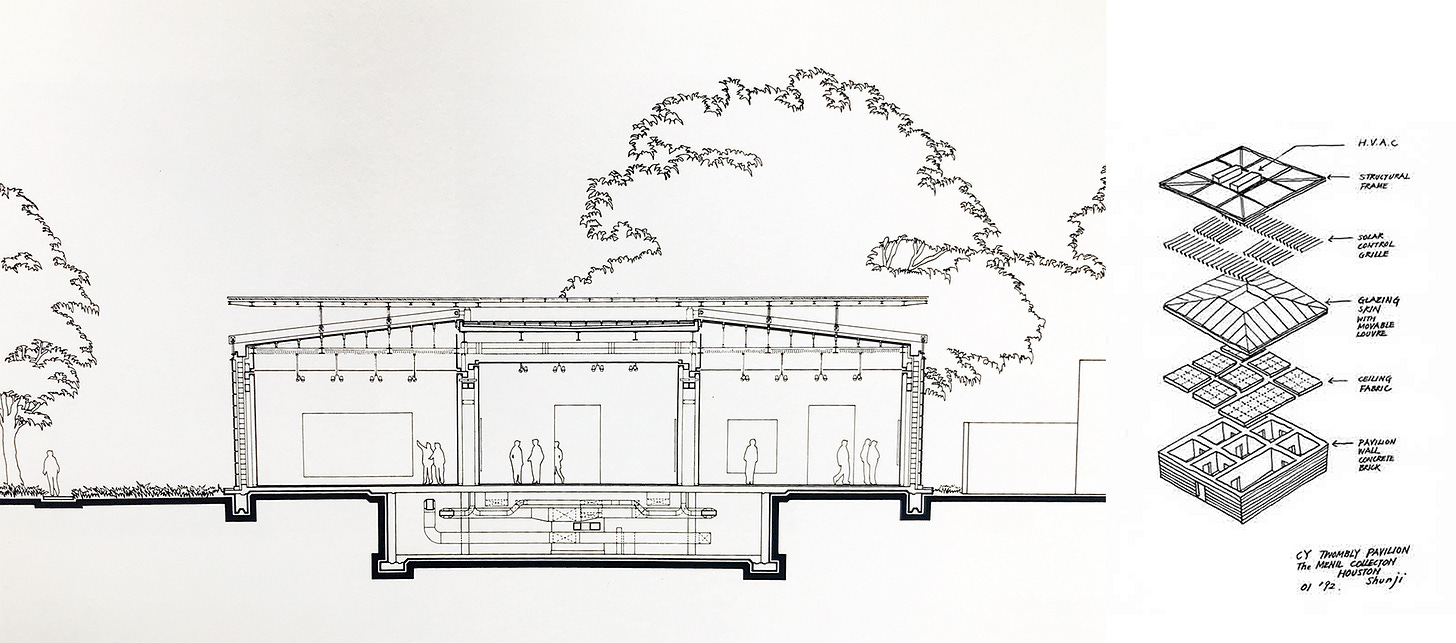

Designed and built between 1992 and 1995 in Houston, this gallery houses the Menil Collection’s works by artist Cy Twombly. The setting is in a suburban residential area, a “grassy campus ringed by bungalows that are also owned by the Menil Foundation. Designed as an unpompous ‘village museum’.”7 Piano’s diagram below contrasts his design on the left with the iconic “hat” roof form of nearby houses:

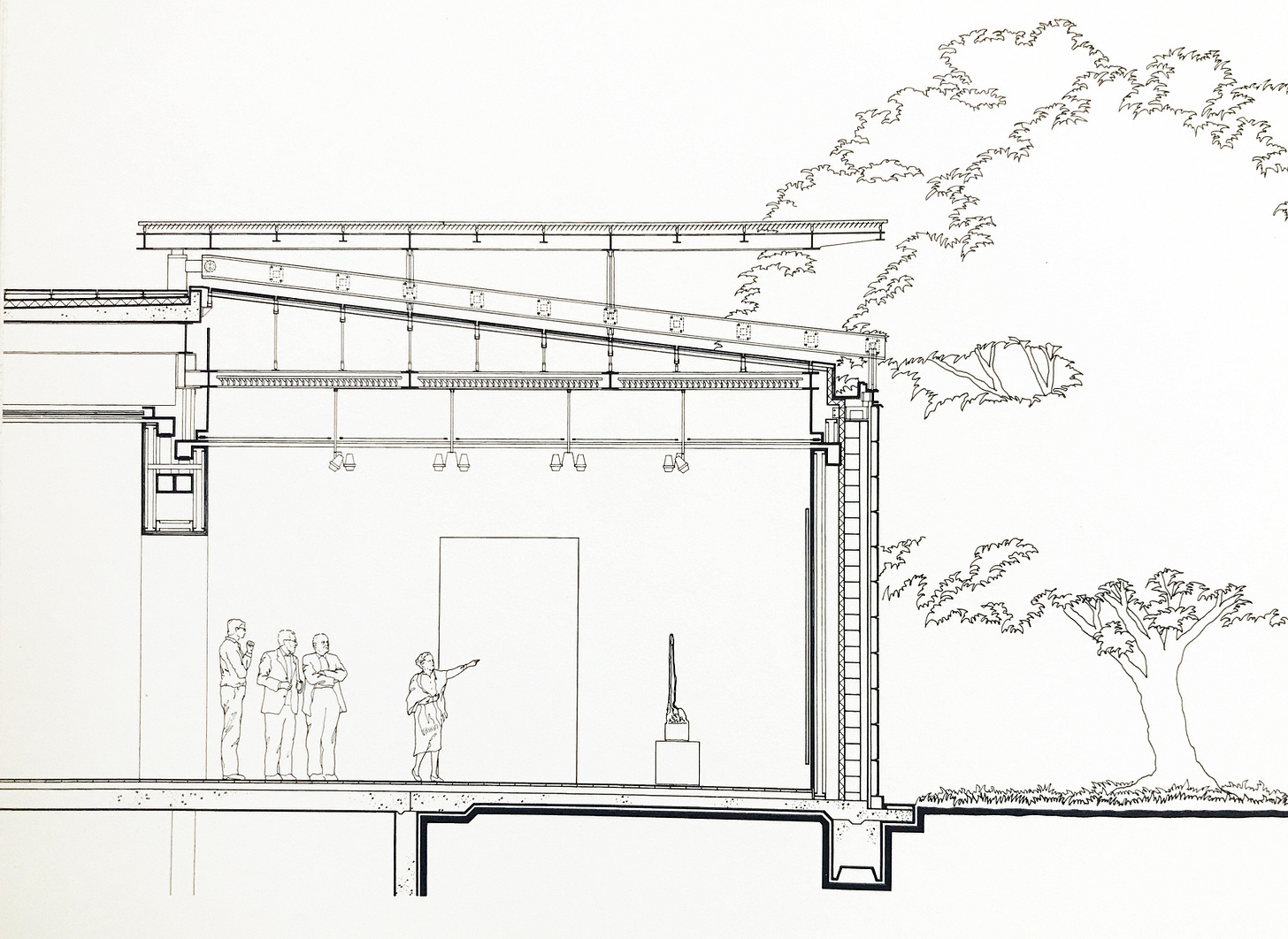

Piano’s buildings often have layered roofs that carry multiple meanings and functions. This roof presents a sheltering plane that hovers above a maze of walls and a solid enclosure, heightening the distinction between inside and outside. Heavy walls guard the precious artwork inside, while transparent and translucent layers of the roof bring in a sublime quality of natural light. Note that both these early design sketches include the sun, trees, and people. Piano’s work always facilitates and celebrates interactions between people and the elements.

Look again at Semper’s four-elements diagrams above. For him the roof came right after the hearth, an important shelter against the hot sun or soaking rain. Having a roof over one’s head is so basic that it’s at the very base of Maslow’s pyramid—a physiological necessity. Far from preventing the roof from rising to the level of metaphor, this necessity is a powerful reason to elevate it to symbolic status.

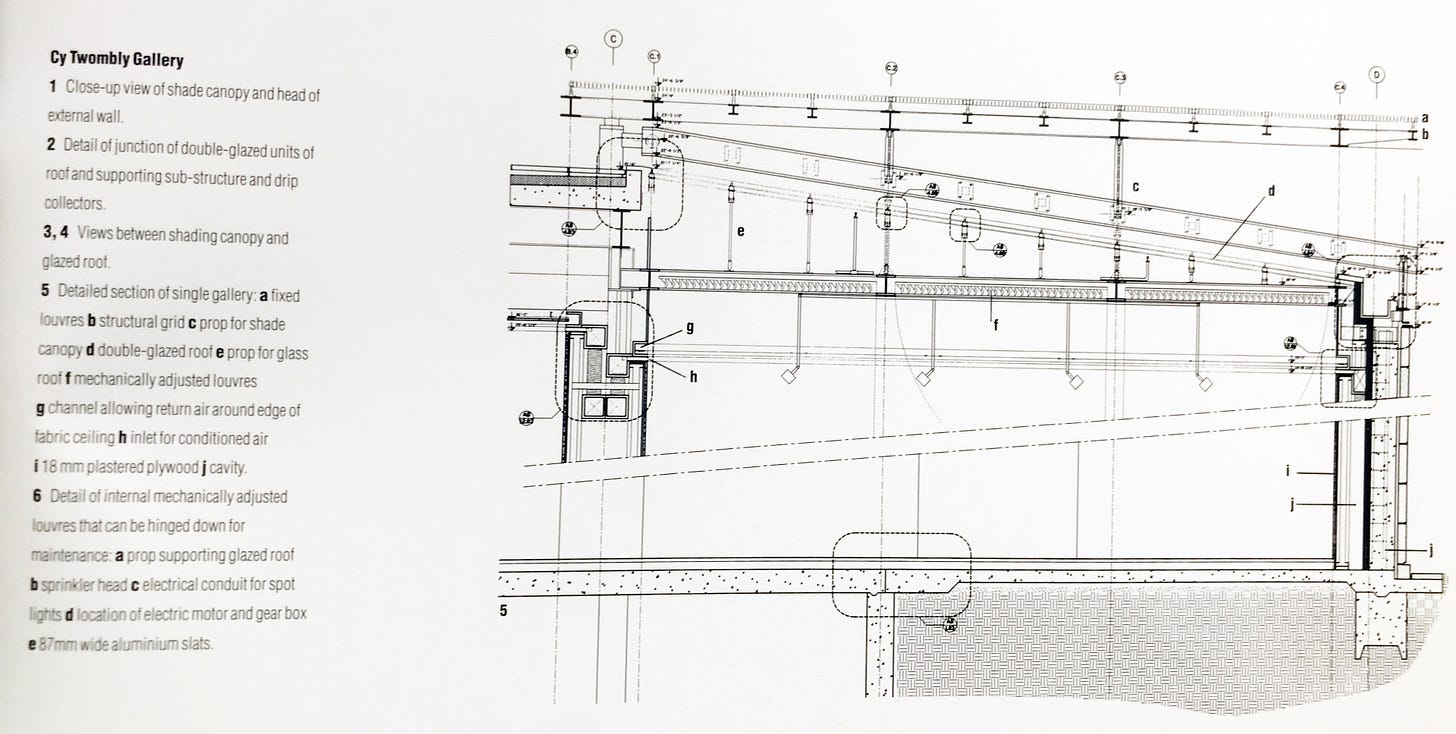

Each layer of the Cy Twombly Pavilion serves a purpose. A roof must keep out weather, shade from direct glare, filter damaging UV light, conceal mechanical equipment and absorb noise, and all those layers must be supported structurally.

For his second building on this campus, Piano chose large stone slabs for the exterior enclosure. These are in direct contrast to the clapboard siding of the houses, giving the pavilion a scale and monumentality suitable to the dignity of its purpose and contents. The heaviness of the walls is also meant to contrast with the lightness of the hovering roof and shading canopy.

Architects sweat over details for both functional and aesthetic reasons. Note the contrast between the heavy enclosing walls and the light, many-layered roof. The sloping layer drains rainwater but is not seen from outside. The topmost frame is the roof’s visible expression, but even that must also serve a functional purpose—in order to justify the expense, it supports louvers that convert the harsh rays of the sun into indirect light.

In the detailed drawing above, you can see that the walls themselves are hollow, to enclose the steel structure (columns and beams) and conceal the heating and cooling ducts. This building is actually a steel frame structure. The roof appears to sail over heavy load-bearing walls, but that is an intentional visual device.

Piano’s practice, called Renzo Piano Building Workshop, uses tons of models like this one to design their buildings, and larger ones to verify technical aspects. For this building, they tested the natural lighting with a 1:50 model at the University of Michigan.

Piano’s obsessive attention to detail results in perfect light on the artwork without the damage of UV, which is arguably the whole point.

I had a ton of fun with this one. It gave me an excuse to dig through these books that were on the floor of my office all summer. If you look closely, you can see my thesis.

Building Hope is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Do you have a favorite building? Did reading this change how you see it, or deepen your appreciation for its roof?

In the comment section of this post, “The book will kill the building,” one of my early forays into writing about architecture here.

Thirty years ago, it was launched as Comprehensive Design Studio, and soon became a standard required course nationally for all accredited graduate programs. A new colleague who joined us last fall and went through the summer boot camp that is our preparation, dubbed it the “Complicated Design Studio.” He’s not wrong.

That’s a lot of French theorists! I picture them dressed up in lacy frippery, wandering the gardens of a Peter Greenaway-type estate, debating what came first, form or technique.

My thesis advisor wrote a book called The First House: Myth, Paradigm, and the Task of Architecture. I was lucky enough to review an early draft and even made it into the acknowledgements. So she was talking to herself as much to me on that day in May.

I don’t want to dump on Le Corbusier too much. He was a brilliant, forceful character who designed many masterworks that hold up as special places even today. That’s a subject for a whole other post. Or a book. Or a multi-volume set.

Peter Buchanan, Renzo Piano Building Workshop Complete Works, vol 3, Phaidon, 1997, p.56

Thank you for presenting this in a way someone (me) with very little knowledge of architectural design could understand! Like art, I know what I like, but having a framework for thinking about the design both confirms my preferences and expands what I can appreciate!

Thanks for mentioning my stack! By the way, Richard and I are not married. I don't believe in marriage. It's not a good idea for women to marry. I do know it's popular. xxL