⬅️ Previous chapter

Mid-September 2009

The road northwest from Scranton, PA snakes narrow and potholed between low stacked stone walls. Tree branches form tunnels overhead. Grace passes tiny towns tired with grime. Machine parts dot yards, porches slump. Junked cars squat on scraggles of grass. On a blind curve, an oncoming water tanker barrels towards her, forcing her to skid through the narrow gravel verge and slide down the dusty ditch, heart racing, swearing, sweating. The water truck that has tailgated her for miles charges by in a whoosh of diesel exhaust. The column of air buffets her small car, the engine stalled and ticking.

With shaking hands, she opens her door and struggles out. The tires seem okay. Didn’t do her suspension any favors. Another truck approaches, all speed and chrome and blaring air horn. She darts around her car to shelter from the aggression. During a lull, she slips trembling behind the wheel and forces deep breaths. The car starts. Working the clutch and gas, she manages to nudge it up out of the ditch onto the narrow shoulder. Re-entering the road, she floors it like Dale Earnhardt after a pit stop.

Grace contacted the owners of the farm adjacent to Warbird to ask permission to place air monitors on their property. They invited her to one of their Radical Self-Sufficiency workshops and promised to discuss her proposal afterwards. Now she’s burning an entire Saturday for something she learned the hard way—by living it. Caroline said to wear old clothes and be prepared for mud.

The timing couldn’t be worse. Two of the four lab assistants Grace hired turned out to be lazy flakes obsessed with “work-life balance,” with terrible listening skills and even worse follow-through. Barbara was pissed at her for letting them go before discussing it. Training new people would fall on her, but now that the semester has started all the grad students are taken.

Truck services dominate the crossroads town where she turns north. A sprawling, metal-sided tire warehouse crowds a dusty white clapboard chapel. The black steeple over the red church door looks like a witch’s hat. A sign on the diesel mechanic’s shop brags: We put the horse in horsepower.

James Cowan is now openly impatient with their delays in ramping up operations. Yesterday, he said, “Why not move this operation in-house?” Meaning, decamp to United Energy’s gleaming office tower in Manhattan. When Grace laughed, he pressed her. “I’m serious about this. And I thought you were serious too.”

How can she explain what that would do to her soul? He doesn’t care that her entire life is organized around the small, engraved brass nameplate beside her door, Evans Lab. Grace’s advisor at Cornell had presented it to her during the bleak time she lived in her car. He was a sonofabitch, so she never quite parsed whether he meant it as motivation or mockery. Probably both. She’d stuck it to her dashboard and touched it every morning before stretching out the kinks from another cramped cold night of subpar sleep.

On top of it all, yesterday, her mother canceled Sunday dinner. Too sick from chemo, she said. Then she refused Grace’s offer of help because her neighbor is an RN. Everything’s taken care of, you’re busy, don’t worry. Is that her mother’s way of asking for a visit? If she must miss a day of work, she should be with her mother, not wallowing in mud with strangers.

The farms she passes on the way to the workshop are being pushed by the energy boom into nostalgic irrelevance. She imagines the remaining farmers living less a dream than a duty. One bad harvest away from auction. Vines cover silos, sheds tumble, a motor home on blocks rusts beside a barn with a tree splitting its roof. Black dots of lonely cows stand, forlorn and bored.

An overgrown hedgerow conceals Dragonfly Farm’s entrance. After three passes, Grace finally spots a carved wood sign with Celtic-looking letters circling a dragonfly, once-bright colors faded and flaking.

The cars in the matted grass clearing hail from four states. Subarus and Volvos. Grace counts seven red, white and blue bumper stickers for Obama ’08. The one standout is a mud-spattered tangerine VW minibus that might have been parked there since Woodstock. The sticker on its pitted chrome bumper—Eat More Kale—could be structural.

Grace treks uphill and finds a small crowd clustered on the far side of the farmhouse. Older couples, young lovers, friends. Skin tones ranging from pale pink to deep brown—far more diversity than in her classroom. Eight kids, toddlers to teens, orbit the group. A white couple in their late twenty’s sports matching dirty blond dreadlocks. Grace pegs them for the VW bus. Most heads are covered with ballcaps, bandannas, wraps, hats. Years of fieldwork as a biologist and now climate scientist and Grace is still not a hat person.

A tall, wiry Black man is speaking. This must be Charles, Caroline’s partner. He’s wearing a frayed flannel shirt as a jacket and a battered straw hat on close-trimmed hair. Crow’s feet bracket his wire-framed granny glasses. His precise gestures remind Grace of a Harvard professor she dated the summer after freshman year. She worked nights at the hospital blood lab and went straight to the morning poetry class she was taking to pad her credits. After class, she and the professor got high together in his tiny furnished apartment. They listened to technopop, read poetry to each other, and hooked up everywhere but his bed. The music and the bed taboo should have been red flags, but he had good weed.

“Every place-based culture has a word or phrase that means collective work for collective benefit,” Charles is saying. “In Chile, it’s La Minga. In Haiti, there’s konbit. You can find this idea everywhere from Algeria to Zimbabwe, and on every continent. Pockets of uncolonized indigenous practices and people reclaiming them.”

“Right on,” says the dude with dreads. “Power to the people.”

An older woman wearing a Yankees ballcap and designer jeans pressed to a crease says, “I was in the Peace Corps in Algeria. Wonderful country.”

Caroline watches Charles with open admiration. Her wavy bob of brown-black hair frames an oval face. She’s sturdy and soft, about Grace’s height. Could be Latina. Or Sardinian, like Grace’s mother. How did she plan to work with mud wearing a candy-apple red velvet swing coat?

Caroline meets Grace’s eyes and flashes a dazzling smile of welcome. Grace nods hello.

Charles lectures on, phrases zested with co-creation, decolonizing, beneficial relationships, pattern thinking, food justice, land sovereignty.

During a lull, Caroline bounds over to Grace, coat streaming behind her like a cape. “You guys, Grace here is a famous scientist!” She draws Grace into a sideways hug. She smells sweet, like fresh-cut hay. “If you haven’t seen her TED talk, you should. It’s brilliant. The Nitrogen Queen on the future of modern civilization.”

Grace squirms at the reminder of her abandoned first love studying marsh nitrogen cycles. She really was the Nitrogen Queen for a hot minute. Methane was to be a few years’ detour at most—long enough to convince the world of its importance. She’s still waiting for the gatekeepers and politicians to start listening. Even these hard-core activist types don’t even bother to feign interest.

Charles resumes his lecture. A small child rockets up to Caroline to show her a leaf. He’s waist-high, big head balanced on a small skinny body. Soft corkscrews of copper, black and chestnut hair spill over his forehead and ears to brush his narrow shoulders. “Miles, Honey, I’d like you to meet someone.”

“My name is Jack, Mommy.” His voice is cartoon high.

Caroline throws Grace a What now? look. “Okay, Jack. This is Grace.”

He offers Grace his small grubby hand. Startling jade eyes glint mischief. He grins a mouthful of tiny teeth. Grace rarely sees kids up close. She marvels that his tipped-back head doesn’t pull him right over. She squeezes his hand with a Meeting-As-Equals grip. “Nice to meet you . . . Jack.” To her surprise, he returns the pressure.

Then he hummingbirds away to join a game of chase with the other kids.

Charles holds forth on the relative merits of different biofuels. “Any time we burn a fuel for heat, that’s an interim solution. We need fuel to dry and can our food, to heat our greenhouse. We should calculate the carbon footprint, but there’s always so much else to do around here.”

An impromptu Q&A follows. People debate the environmental costs of heating with any type of fuel, fossil or bio-based, versus trucking food from afar, versus solar hot water radiant floors. One argues for harnessing waste heat from the nearby chicken house. The hair-splitting becomes a virtue competition.

Grace is bewildered. The farm is a few hundred acres surrounded on all sides by the heavy industry of methane extraction, not some kind of utopia. What’s the carbon footprint of one organic farm compared to hundreds of gas wells? Instead of calculating emissions from canning food, why not march in the streets with their neighbors? If they even know their neighbors. Which is understandable. She spotted a confederate flag stretched between two porch pillars on a house just up the road.

Walking to the workshop site, the group passes a chicken yard. Miles scoops a hen from the wrong side of the fence and, with touching care, passes it to his mother. The rust-colored chicken melts in her arms. “These gals are the stars of the show. Just ask them,” she says. Her head-stroking elicits a soft cluck and narrowed eyes. If chickens can purr, this one is.

The group arrives at a hip-high, three-foot ring of stacked rubble from a torn-up sidewalk. Concrete chunks fill the ring to halfway. “We call this urbanite,” Charles says with a smile. “Don’t throw it in a landfill. Find uses for it. Make new things.”

“Reuse before recycle. Smart,” says a woman with pink cheeks and white hair in a long braid.

Tools and materials stand in readiness like ingredients for a cooking show. Caroline had given Grace no details; now it’s too late to ask. Several participants hunch over journals and notebooks, eagerly scribbling Charles’ instructions. A few take photos with their phones.

Grace massages her temples, willing her headache away. There’s a tug on her sleeve. Miles is there, dazzling her with his jade eyes. She blinks, forces a smile.

“I have a secret,” he says in his baby voice.

“Oh? What is it?” Her fingers twitch with longing to touch his mess of soft curls.

He cacklesqueals. “Silly! It’s a secret!” and jets off to pull an empty beer bottle from the wooden crate near Charles. Miles pretends to drink from it, deftly dodging his father’s reaching hand.

Someone jokes about the hard work to empty all those bottles. One or two people laugh. The dreadlocked couple shares a private eye-rolling moment.

Charles shows how to nestle the bottles on their sides atop the rubble in the base. “The air pockets in the stacked bottles insulate beneath the oven to prevent heat loss downwards.”

Grace doesn’t see how it’s going to be an oven. Or why. Several people record Charles’ thermal mass lesson in their journals. The woman beside Grace sketches a cross-section of the arrangement and labels it like a diagram in an engineering journal.

These feel-good activities that preach individual salvation depress Grace. They’re a distraction that gives multi-nationals a pass to trash the planet.

Caroline places a quart Mason jar with care into Miles’ small, eager hands. “Time to get muddy, folks,” she sing-songs. “We’ll pack cob around the bottles as we stack them. Once the ring is full, Charles will demonstrate the next step.”

Miles walks solemnly to keep the muddy water still. People admire the lighter and darker stripes that have settled out. “This is a simple way to determine the ratio of clay to sand in your soil,” Caroline says. “You need clay’s stickiness to hold the cob together. Clay is heavy, so it settles to the bottom. This way you can see if you have the correct balance.”

People ruffle Miles’ hair. He grimaces and squirms away, jostling the jar. The engineer turns to a clean page to draw the jar and label its soil layers.

The only cob Grace knows is from eating sweetcorn. Over an hour burned already. She should ask Caroline to meet now. She should be back in Baltimore, checking on her mother.

It’s hot in the sun. Charles removes his plaid shirt to reveal a faded tee with the pink “Sopranos” logo over words whisper-shouting “FAMILY. REDEFINED.” Grace tosses her black jeans jacket on the ground. Caroline sheds the red coat to reveal tan canvas coveralls and a plain white t-shirt. It’s like watching a butterfly turn back into a caterpillar.

The adults spread two large blue tarps on the ground. The kids jump and wrestle on them. People shovel soil and dump sand on the tarps, then spray water over the piles. Grace catches the telltale rotten-egg smell and bends to sniff the water. Could be the mud, hard to tell. She wonders if it’s already too late to baseline their water. Not that water is her thing. She can hear her father and every advisor she’s had. Stay focused, Grace. It wouldn’t surprise her if Dr. Margherita Hack starts in on her, too. She quickly distracts herself from the thought. Last thing she needs is to encourage another of her visitations.

“Let’s mix some cob, people,” Caroline says. Everyone, kids and adults, crowds barefoot on the tarps to stomp and tromp in the lumpy orange mess. Grace peels off socks and steps in the corner of the least rowdy bunch. The metallic smell of wet earth and the squish of mud between her toes transports Grace to the year she turned eight. When she lived on Holland Island with her grandparents while her mother and father blew up their toxic marriage. She squished and squelched in the gooey mud of marshes and tidal creeks, hunting the pungent reek of life for treasures. No shoes, not even in winter. In spring, she sat reed still in the shallows to watch crabs mate.

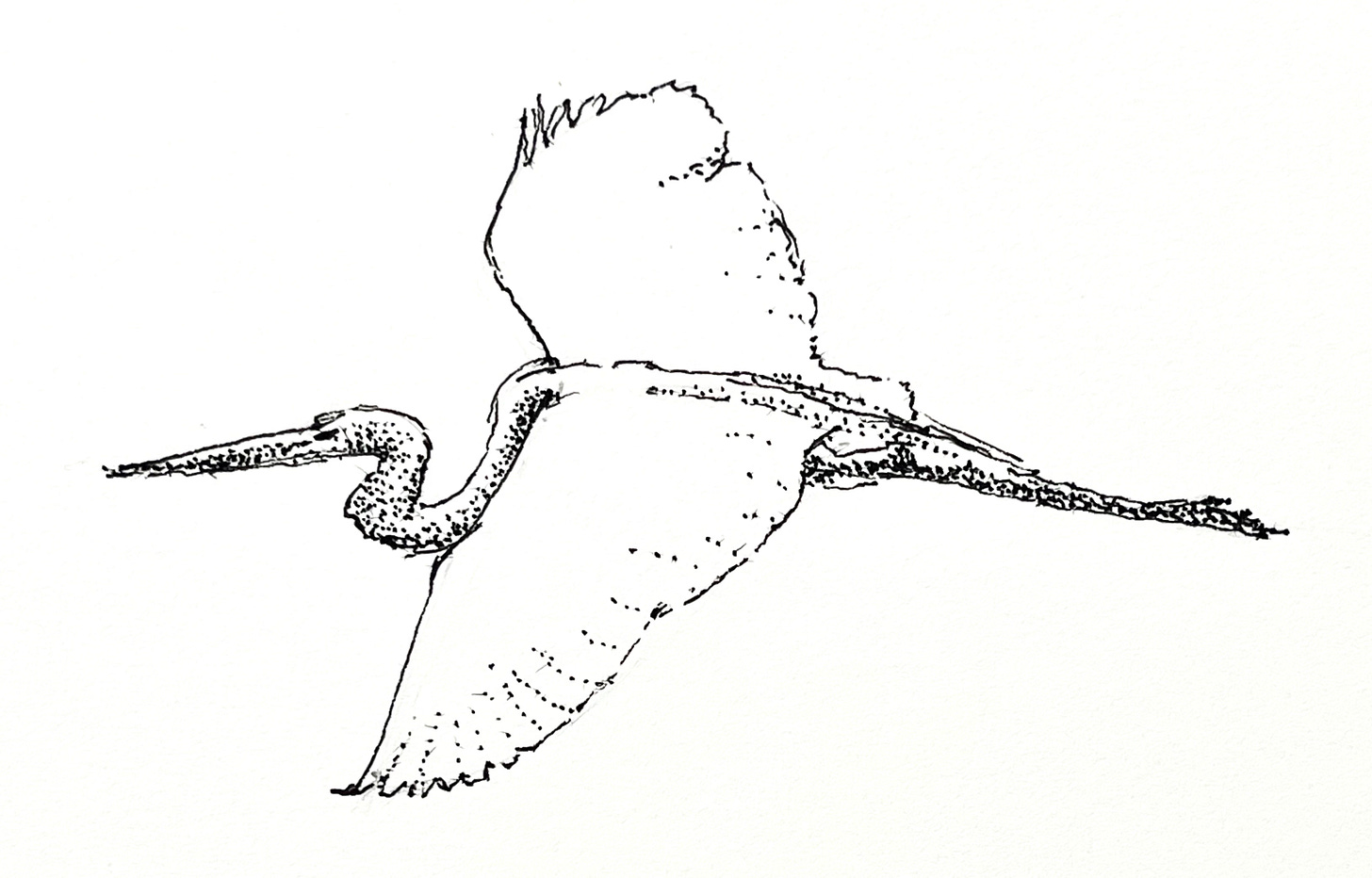

The blonde woman steps barefoot onto the tarp to help mix mud. She flips her dreads, revealing a tattoo of a standing heron on her neck.

The herons on Holland Island modeled a communal family life that Grace still admires. Solitary stalkers for most of the year, they hook up in February to build nests in a communal rookery with dozens of other herons. The pairs face each other standing on twig legs and tap beaks in affection. They incubate the pale blue speckled eggs in turn and raise the young together. In May, they part ways, no regrets. Grace’s grandfather told her that every year they choose new mates and build new nests. As a girl, she paddled the old wooden skiff through a maze of cuts and cricks to watch the rookery with borrowed binoculars. She shivered in February’s wind while the birds hunched and swayed in bare treetops. Male herons brought twigs for the females to tuck and weave and wrestle into nests.

Kids and adults toss handfuls of straw onto the mud, now the color and feel of peanut butter. A comedy of short and tall bodies tilt and lean at odd angles, bumping each other, trying not to topple. Grace presses her heels and grips her toes to tramp the tickly straw into the mud. She loses her balance and falls into a guy with a dense body and great arms. He grips her shoulders to steady her, their faces inches apart. A thick rope of desire twists up the center of her body, but before she can say anything, a woman pulls on his arm from behind, saying, “Babe?” He dips his head and turns away, leaving Grace to her lust.

Kids sprawl on one of the tarps to make volcanoes and smear balls of mud in each other’s hair. Miles and the other boys are shirtless, digging for dinosaur bones. An older girl sprays water on them to shouts and squeals until an adult confiscates the hose.

Grace joins the group forming loaf-sized balls of the clay-mud-straw mixture. They toss the balls to the builders gathered around the base, who jam them among the bottles. When the top layer is smooth, Charles drags a two-by-four across to level it. He displays a thin brick, then presses it into place. “These firebricks will form the floor of the oven.”

Grace doesn’t see it. What’s the point? How is this any kind of oven? With a methane apocalypse at their doorstop, they’re making mud pies.

Grace pictures each of them going home, so inspired to build their own cob ovens that they won’t even bother to change their mud-caked clothes. They’ll grab a shovel and start to dig, right there in the back yard, because who needs a grass lawn, anyway. And in a frenzy of industriousness, they’ll sledgehammer their patios and sidewalks, some of them thinking as the blows land of their sadistic boss, or maybe a surly teenager. Their penance for being Americans, for their whole materialistic existence—a tangible shot at redemption, finally, after so long a search.

And cob ovens will sprout in suburban backyards and city lots all over the land, the smell of wood-fired pizza rising like incense in a church. Causing warriors to lay down arms and politicians to co-sponsor bipartisan climate bills, and well drillers to dismantle their rigs and head home for pizza night with the kids.

In April and May, when the baby herons emerged with the new leaves, Grace shoved her skiff through thickets of thorny greenbrier and poison ivy under a cacophonous canopy of screeches and squawks. If her boat drifted downwind, the black stench of dropped fish and fallen young coated her throat. The chicks’ dandelion heads on downy bodies surrendered to the swamp. That such elegant birds could emerge from that ugliness impresses her still.

. . . to be continued. . .

Next chapter ➡️

I was going to post a still photo, but decided why not include a video instead? If you search “cob oven build,” you’ll find many DIY workshops, each with its own variation on themes.

One of the best things about reading serial fiction on Substack is the community that gathers around. This is slow reading at its best. Twice a month, everyone experiences a new chapter and gets to weigh in on what’s happening in real time. When I’ve read stories this way, whether short fiction or whole novels, the interactions with both readers and authors is one of the most enjoyable aspects.

Each season, we donate 30% of paid subscriptions to a worthy environmental cause. This season, it’s Women's Earth and Climate Action Network (WECAN) International. For The Earth And All Generations - Women Are Rising For Climate Justice & Community-Led Solutions. Track past and current recipients here.

Grace’s knowledge butting up against futility is so funny, but also enlightening. Her sarcasm meets my own daily attempts to make a difference while the lords of commerce and energy turn the other way. This paragraph cracks me up!!! (But also kind of makes me want to cry.) “And cob ovens will sprout in suburban backyards and city lots all over the land, the smell of wood-fired pizza rising like incense in a church. Causing warriors to lay down arms and politicians to co-sponsor bipartisan climate bills, and well drillers to dismantle their rigs and head home for pizza night with the kids.”

I share Grace's impatience with personal carbon footprint calculus, standing in the shadow of corporate giant waste. Yep I do my best. Nope I don't think my trusty compost pile and rinsed out ziplock bags are changing the world. 💚