Dear reader:

This post is part of

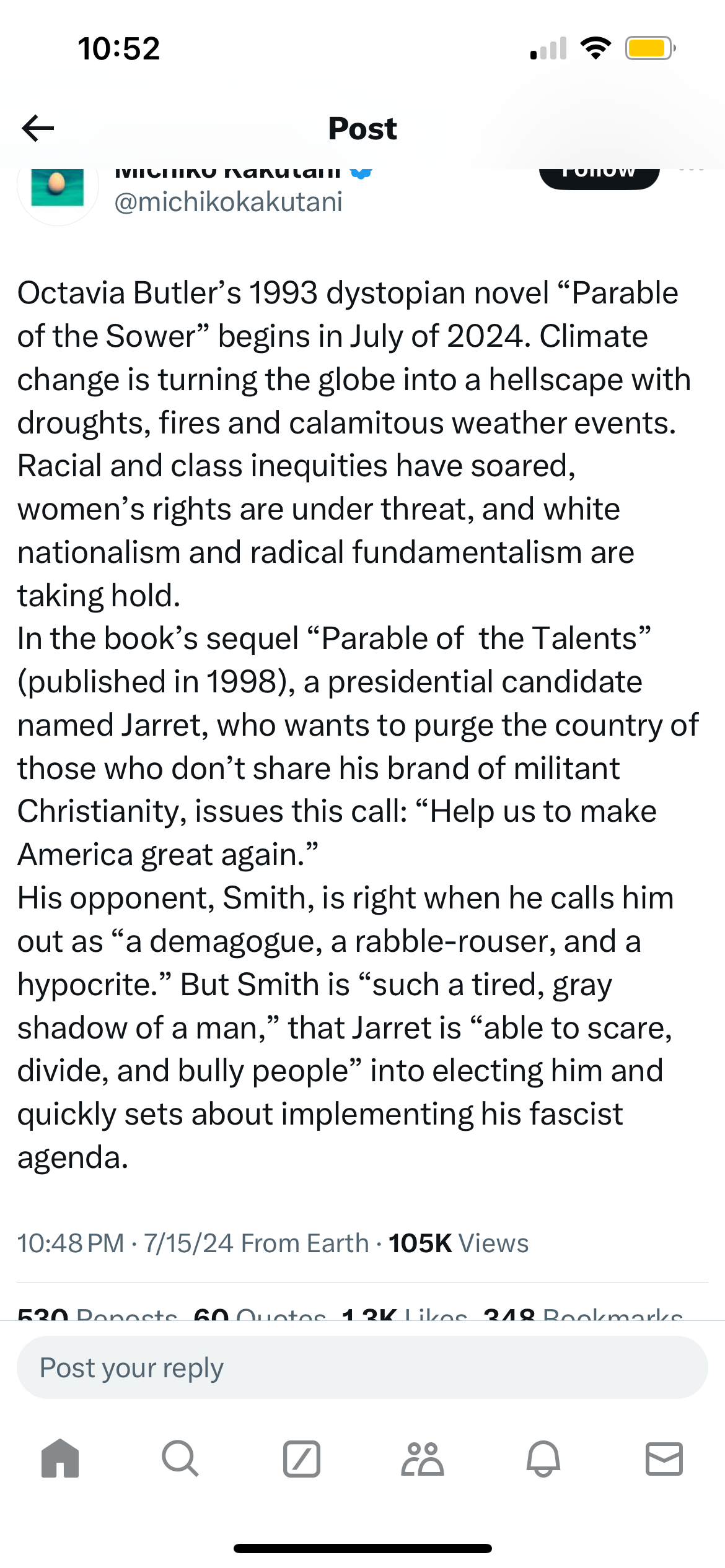

’s community writing project called “Enchanted by a Book,” hosted by Quiet Reading with Tara Penry. In July 2024, Substack writers are joining together to spread the joy and revelation of reading and the unique experience of every reader with a book. Find a complete list of participants at the project home page, where new links will appear all month.Octavia Butler’s 1993 book Parable of the Sower so enchanted me four years ago, I didn’t clock that it’s set in July 2024. <pause to let that date sink in> Yes, that’s RIGHT NOW. Doesn’t every point in this tweet blow your mind?1

Dystopian demurral

Dystopian fiction is a red flag for me. I’ve got no time for it. We have enough dystopia, too much—an unhealthy, over-indulgent amount of deeply dark futures. To what end? Especially lately with the accelerating unraveling of, well, everything. When too many are living actual dystopias and have been for too long.

Remember, stories not only reflect reality; they create reality. The power of our imaginations and collective beliefs creates the world we inhabit, today and every day. Storytelling is a sacred calling as much as a form of entertainment. Simply extracting a slice of present reality into a bleak future is lazy and irresponsible at best.2

But let’s get real. Cautionary tales have their purpose. Since I write climate fiction, I do read some of it—especially stories conjured by talented writers and laced with moments of humanity and hope. I can highly recommend The End We Start From, Station Eleven, My Monticello, How Beautiful We Were, Strange as This Weather Has Been, Gold Fame Citrus, Weather, Bangkok Wakes to Rain, and Atwood’s Oryx and Crake trilogy. I would say, give a pass to hyped books like Odds Against Tomorrow and (unpopular take) Ministry for the Future. Haven’t read The Road.3

Butler is a shining exception to my obstinate embargo. Parable of the Sower avoids sensationalizing dystopia, while managing to gaze straight into evil. The darkness is balanced by deeply spiritual ideas. I read it in my first semester of a fiction MFA program during the global pandemic and a fraught U.S. election year.

And here we are now, in July 20244: the planet is on fire, the U.S. election is even more insane than in 2020, our Supreme Court strips rights and destabilizes institutions with impunity glee, fascists proudly published a fancy game plan5, corrupt war criminals bomb children in multiple wars, and a majority of Americans, when asked, say the economy is their number one concern. I mean, really.

Dystopian divination

Margaret Atwood’s 1985 dystopian novel, The Handmaid’s Tale, gained a new audience with the 2017 TV series on Hulu. Interviewers and critics called Atwood a prescient predictor of the future. Then, on June 24, 2022, the Supreme Court issued their landmark6 Dobbs decision.7 That one act stripped (at least) half of U.S. citizens of their 50-year-old Constitutional right. Boom. Done. Another round of interviews and opinion pieces citied Atwood as an uncanny prophet.

She has said that she approached the novel as a thought exercise. She chose a few typically American traits—our fundamentalist origins, fascination with strongmen, our misogyny and casual violence—and stirred them into a big pot of “what if?”

Butler’s story has a similar truth-ring to it. She is known to have read widely and was a prodigious researcher. After a brief unmethodical search, I didn’t turn up a specific reference to Atwood as an influence. Butler’s imagination was plenty fertile, her mind well-stoked by the likes of Bradbury, Sturgeon, and Heinlein, plus primary sources galore. I hold to her cautionary tale for its inclusion of the light with the darkness. I’ve long believed, as an environmentalist, that our problems are at least equally spiritual and metaphysical as they are practical and material (possibly more so).

Dystopian dexterity

After devouring this book, I dissected it.8 My aim was to discover even a smidge of how Butler wove her spell so completely. Chapter 14 is a pivotal scene of shocking violence, so I studied it in depth. Made a chart to track every word paragraph by paragraph, with columns for nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs.

Butler delivered. The entire chapter contains a mere 15 adverbs and a sparing use of adjectives. The action is direct, well-supported by well-chosen nouns and her brilliant use of strong verbs. Sometimes verbs are repeated, echoing across paragraphs. A few examples: escaped, burning, shouted, grabbed, herded, running, screaming, shooting—you get the idea. Seeing the evidence of her mastery, verb by verb, changed me as a writer. Verbs are everything to me now.9

Dystopian tao

Trigger warning: language depicting violence (esp. toward women) and death.

Lauren is the first-person narrator of Parable of the Sower. She is fifteen, it’s July 202410, and things are very bad. The novel unfolds as a series of journal entries moving sequentially through time, until the final entry in October 2027. Early on, her father advises her that the plain truth scares people and makes them resistant and distrustful. Instead, he advises:

“If you can think of ways to entertain them and teach them at the same time, you’ll get your information out. All without making them look down [into the abyss].” (p. 66)

I love how meta that is. In two sentences, Butler lets us in on what she’s doing and why. Sign me up.

The journal is an intimate space that develops Lauren as a character and builds the world in which she lives. Lauren alternatives between sharing her thoughts on God and reporting on the happenings in her community and family. Lauren’s father, who in better days was a pastor at a local church, is one of the leaders of their small community. Outside the gates of Lauren’s walled, eleven-house cul-de-sac, it’s hell. There are rotting corpses, people with missing limbs and open sores. Women who’ve been gang raped stagger about naked and dazed. Everyone is armed. Even kids learn how to shoot.

Lauren is black, which she doesn’t mention until chapter 4. She was born with “hyperempathy syndrome” to a drug-addicted mother who died in childbirth. Lauren can feel the pain or pleasure of other people. She is learning to navigate this power/curse/disability by averting her eyes when she can.

She is a deep thinker with a strong sense of both justice and survival. She has a way of taking things as they are with none of the adults’ nostalgia for the old days. Doing the math, Lauren was born in 2010. In the world of the book, she never experienced this country at its best (whenever that was, if ever). She knows only decline, chaos, and violence. Her father and stepmother have taught her practical skills: growing food, educating children, and community-building.

The plot unfolds in a straight line, much like the roads that Lauren and her companions must walk as they work their way north hoping for a better life. Lauren’s history is presented as part of the forward-moving narrative. There are no side trips. Each character she encounters along the way has a story. There are echoes and parallels of the same suffering—arson, beatings, murder, driven out of their homes. Always, the writing is uncluttered and spare:

“Walking hurts. I’ve never done enough walking to learn that before, but I know it now. It isn’t only the blisters and sore feet, although we’ve got those. After a while, everything hurts. I think my back and shoulders would like to desert to another body.” (p.143)

The simple structure leaves space for ideas and spiritual philosophy. The central what-ifs pile upon each other to create a dangerous world: what happens if extreme drought makes water nearly unobtainable, if essential services (police, fire, ambulance) are privatized, if illegal drugs are so powerful that addicts become violent predators, if politicians grow more powerless and useless, and if corporations purchase and run cities for profit?

The worldview underlying this is a worship of power and money and material goods, tied to hyper-secularism that leaves people without common values, purpose, or empathy. The forces behind Lauren’s world ring disturbingly true today.

Lauren journals on:

“I’ve finally got a title for my book of Earthseed verses—Earthseed: The Book of the Living. There are the Tibetan and the Egyptian Books of the Dead. Dad has copies of them. I’ve never heard of anything called a book of the living, but I wouldn’t be surprised to discover that there is something. I don’t care. I’m trying to speak—to write—the truth. I’m trying to be clear. I’m not interested in being fancy, or even original. Clarity and truth will be plenty, if I can only achieve them.” (p. 84)

Lauren’s journal is a record of the transmissions she is receiving about Earthseed, as well as her optimism that periods of renewal follow dark times. Her spiritual awakening reminds me of The Great Transformation, Karen Armstrong’s brilliant chronicle of the Axial Age (9th century BCE) when the world’s great religious and philosophical traditions all emerged in response to humanity’s suffering. That same sense of personal reflection, responsibility, and enlightened action pervades the hopeful messages of Earthseed.

What did you enjoy most about this essay? Have you read Butler’s book, Parable series, or other books? You can find other posts in

’s marvelous community project, “Enchanted by the Book,” at the project home page.If you enjoyed this post, a lovely ❤️ keeps me going. Another way to show love is to share this post with others by restacking it on Notes, via the Substack app. Thanks!

Last Sunday’s news from the Biden campaign at least makes the final point moot . . . right? I for one am excited about the future in a way I haven’t been in a long while. 🥥 🌴 iykyk

I know, I know. Come at me.

Did I mention it’s the actual date of the book’s opening?

Read the whole mess on the Project 2025 website.

Is that what we’re calling it now?!

Of course, we already knew what was coming, because “someone” had leaked the draft opinion on May 2, a “someone” who was never discovered; looking at you Sam Alito, or maybe it was Martha Ann, as she hoisted an insurrectionist’s flag.

I admit that’s an odd image. Bear with me?

I hesitated to write that, lest this very essay belie my claim.

I.e., NOW

I always wonder why Margaret Atwood’s dystopian portrayal of a future when women are reduced to breeding stock is used as a metaphor for the plight of women when so many women in the world actually live in a much worse real dystopia.

I’ve witnessed and intervened in many injustices toward women over the years. I threatened two police officers in Haiti who were beating a woman with their rubber truncheons. I’ve had to intervene to get permission for women staff to travel for training or who were bullied by government officials or religious police. I’ve revised pay scales to pay for positions regardless of the person’s sex.

With so much abuse against women around the world, why must we use metaphors? To me the face of female oppression is a lace eye covering on a black burqa or the young women in Iran who are arrested and in some cases murdered because they refuse to wear hijab.

If I was younger, I would have figured out a way to help women in northern Iraq fight against those who sold them into sexual slavery or worse. They are my mothers, sisters, and daughters.

If you haven't read Kathryn Davis's _Duplex_, I highly recommend it. Believe it or not, a robot narrator. I read it in two sittings. Brilliant. Even wrote Davis a fan letter and she replied. I may do a series of brief review of a variety of books soon ... xo ~ Mary